British Army soldiers training at Lolldaiga area in Laikipia County on November 14, 2022.

In Africa, during the Cold War, both Britain and Israel shared a common Western interest; to counter Soviet influence and to stop the spread of Communism. But in pursuit of these, they used different strategies which at times put them on a collision course.

While Britain maintained a tight grip on its strategic former colonies such as Kenya, Israel, driven by its own security concerns, was trying to outmanoeuvre the British and infiltrate these countries’ security fields. This was the case in Kenya where a trove of declassified documents reveal how Israel and Britain had a bitter rivalry to control the armed forces and other security services.

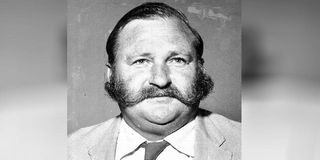

Playing both sides was Bruce McKenzie, an influential Kenyan government minister with extensive business interests, who was also suspected of being an Israeli Mossad and British MI6 spy. According to previously restricted archival material marked “confidential,” at one point a senior British official at the Foreign Office in London instructed the British High Commissioner in Nairobi: “Given that the Israelis often set in a manner detrimental to our interests when they infiltrate into African countries, our aim should be to hold them so far as we can to their present position in Kenya. We would certainly agree that confidence between the Kenyans and ourselves during consultations on security matters would be shattered should the Israelis, as a third party, be allowed to join us. They are of course also devious.”

Bruce Mackenzie

Israel’s effort to outmanoeuvre the British and establish a foothold in the security sector dates back to the period leading to Kenya’s independence. As the wind of Black nationalism swept across the continent in 1960, the Israelis began strategising how to secure their interests and achieve their geopolitical goals in a future free Africa by first befriending African nationalists.

Kenyan nationalists

Before Kenya’s independence, Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs had already come up with an idea of opening a consulate in Nairobi, which was also to serve as a backdoor channel for engagement with Kenyan nationalists such as Jomo Kenyatta, Tom Mboya and Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta (left) with then Vice President Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.

To serve as consul-general was Uzi Nedivi, a veteran Israeli diplomat who had worked in Burma and was part of a team tasked with courting African nationalists throughout the continent. However, plans for an Israeli consulate were blocked by the British, who feared that it could exacerbate the growing anti-colonial sentiments.

With their plan foiled, the Israelis devised another covert scheme, which involved sending author and diplomat Asher Naim to establish contact with Mzee Jomo Kenya by masquerading as an assistant to Israel Somen, a prominent Jewish Kenyan politician and businessman, who had served as the mayor of Nairobi between 1955-1957.

Unlike Nedivi, Naim was little-known and it was believed he could easily establish contacts with African nationalists without arousing suspicion of colonial intelligence. As soon as he arrived in Kenya in October 1961, Naim left for Gatundu where Jomo Kenyatta was still under restriction after being transferred from Maralal.

Since he had no appointment and every visitor had to seek permission from the District Commissioner before seeing Mzee Kenyatta, he was subjected to a thorough interrogation at the gate by colonial policemen guarding the residence. He was eventually allowed to enter after he identified himself as an Israeli with a special message to Mzee Kenyatta.

Nation building

His message to Mzee Kenyatta, according to documents seen by the Weekly Review, was that Israel was ready to assist Kenya in nation building owing to its experience of integrating Jewish immigrants from over 70 countries. Drawing similarities between Kenya and Israel, he pointed out that Kenya had 40 different tribes which needed to be integrated into one united independent nation and that Israel was ready to assist in this process. He also suggested other areas of cooperation such as agriculture and youth movements.

After this successful meeting that laid the foundation for future strategic partnership between Kenya and Israel, Naim made his way back to Nairobi. But unknown to him, Governor Patrick Renison had already received details of his secret visit to Gatundu and instructed his personal assistant to give him a firm warning.

As soon as he retreated to his hotel room in Nairobi, he received a phone call warning him that Mzee Kenyatta was still under restriction and all visitors had to seek prior permission before any meeting. For a time even Somen, who was to act as Naim’s boss during his covert operation to court Mzee Kenyatta, feared that he could be deported.

It was, therefore, decided that Naim should again pay Mzee Kenyatta a secret visit the following day to finalise details of their talks before he could be expelled. According to Naim when he informed Mzee Kenyatta about what had transpired he replied, “My friend, don’t worry. If they send you out, I will receive you in Nairobi personally after our Uhuru (independence).”

With the rivalry heightening after independence, on November 7, 1968 the then Israel Ambassador to Kenya Zev Levin sought to calm matters down when he visited the British High Commissioner to Kenya Sir Eric Norris and assured him that Israel had no wish at all to try to supplant British assistance to Kenya in the security field. According to details of the conversation marked “confidential”, he pointed out that Israel’s involvement in Kenya was mainly driven by concern about the stability of Kenya in light of the happenings along the Red Sea coast.

However, he observed that the Israelis had special knowledge acquired in various fields, which could be useful in Kenya at any time, but they wished to leave it to the British to approach them in case the skills were needed. Ambassador Levin also pointed out that Israel did not want to be involved in Kenya permanently but rather had in mind small training teams which could visit Kenya to carry out a specific piece of training then leave.

Sir Eric Norris reporting about the meeting to his seniors at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in London warned: “We should of course be unwise to accept Levin’s declaration at its face value. We had a bitter taste in May 1967 of the way in which the Israelis are prepared to work diametrically against us.”

Dr Njoroge Mungai.

He went on to cite a case in which the Israelis deliberately invited Dr Njoroge Mungai, the Minister for Defence, to visit Israel at a time when he had been invited by Her Majesty’s Government to the UK. According to Norris, the Israelis secretly tried to put pressure on Mungai, who was shopping for arms, not to visit Britain and instead deal with them. The British diplomat went on to reveal that it was only President Kenyatta who saved the day when he issued orders to Mungai to visit London.

In his further complaints in the declassified report, Norris stated: “I understand that three years ago the Israelis also made some Machiavellian attempts to usurp the position of British advisors in Kenya Special Branch. They also have a purely commercial interest in selling equipment to the Armed Forces; the Kenya artillery battery is already equipped with Israel manufactured Tampella mortars.”

Security fields

While Norris informed his seniors in London that it would be better if Britain saved some money by allowing Israel to undertake certain jobs in Kenyan military and security fields, he warned that it was a double-edged sword because, “in other African countries where they have a foothold such as Uganda, Israel advisers have not contributed to stability, have put people’s backs up and have exacerbated tribal and other dissensions.”

He went on, “Moreover, when it comes to the point, they are not generous in their aid and have, for example, tried to make the Kenya Ministry of Defence pay through the nose for spare parts for the Tampella Mortars.”

In conclusion he stated, “Despite these reservations, I am sure we should take note on Levin’s suggestion and try in the future to maintain some degree of dialogue.”

His seniors in London supported most of his arguments with one correspondent from the East African Department at the Foreign Office stating, “While we realise that you may have difficulty in avoiding discussion with your Israeli colleague should he take the initiative in raising this subject, we here believe that we should consider the position as being that neither we nor the Kenyans want to see the Israelis interfering in the training of the Kenyan armed forces , and that we should avoid providing them with any opening for even continuing discussion of the subject.”

Today Kenya and Israel enjoy strong diplomatic, economic and security relations. The Israelis have sold Kenya arms, trained security personnel and collaborated with Nairobi in a number of projects on renewable energy.