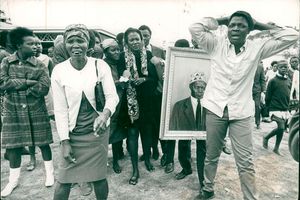

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta and (inset) former long-serving Provincial Commissioner the late Eliud Mahihu.

Kenya’s Presidential Library simply describes the death of the country’s first president Jomo Kenyatta as “dying in his sleep”.

A new book by one of the people present when Mzee Kenyatta was declared dead now paints a more frantic picture as it relays the order of events in that demise in the wee hours of August 22, 1978.

Going as far as reproducing notes written by three doctors to confirm that Mzee Kenyatta was indeed gone, the new book by long-serving Provincial Commissioner (PC) Eliud Mahihu reveals details of an empty oxygen cylinder at a time when the gas was needed to help resuscitate Mzee Kenyatta and a screaming First Lady Mama Ngina who woke up her children when it was clear that death had occurred, among other details.

The book is an autobiography published posthumously, as Mahihu died in April 2008. Mahihu’s death occurred about seven years after he had finished writing the manuscript of the book with the assistance of a journalist.

Mahihu’s daughter Lucy Wacu Yinda writes in her foreword to the book that she found the manuscript when arranging her bookshelf — years after her father’s death.

The book, titled “Eliud Mahihu: My Story”, is published by Mvule Global Profiles and Biographies Nairobi.

Mahihu writes that after Kenyatta’s death was confirmed by three doctors, he rang the Vice President, Daniel arap Moi, to relay the news. Mahihu was then the Coast PC and one of the closest confidantes of Kenyatta.

So close were they that he is the one who discovered that Kenyatta had fainted in a toilet at the last public function he had on his last day alive. Kenyatta took too long after leaving the dais and Mahihu felt something was amiss. When he went to investigate, he found him immobile in the toilet, propped him up to his feet and “tidied him up”.

Fingers have always been pointed at Kenyatta’s handlers for letting him attend events while ailing, with former presidential pressman Lee Njiru once describing it as “being surrounded by hyenas”. It is telling that Mahihu describes one strange trait of Kenyatta’s: He never wanted to admit that he was sick.

“He would never admit to sickness even under great pain. At times it would be very frustrating to know that the old man was in pain but you could not help him because he would not admit it in the first place,” he writes.

The fact that Kenyatta could not give a speech in his last public appearance, however – only muttering “harambee” six times after Mahihu prodded his sleepy, detached self – showed that something was wrong on his final day alive. However, Mahihu writes, doctors who were called to inspect Kenyatta thought he was not in any danger and recommended rest.

After Kenyatta’s death was confirmed, Mahihu also called Geoffrey Kareithi, the head of civil service, and Mr Mwai Kibaki, the Finance minister.

That act of informing Vice President Moi, whom some people around the founding president did not want to succeed Kenyatta, attracted scorn towards Mahihu from the clique better known as the “Change the Constitution” movement.

The scorn, he writes, gave credence to “a story in town that some people had planned to hide the news of Kenyatta’s death for about two weeks, during which time they would effect change to facilitate their takeover of the government”.

“Such changes would purport to come from the Office of the President. They would start with a Cabinet reshuffle in which Moi would be dropped as Vice President,” writes Mahihu.

Mahihu recalls some of the instances when he would alert Mr Moi when the “conspirators” were around Kenyatta.

“Vice President Moi often featured in conversations with Kenyatta. I was able to pick out the main details … and would always make it a point to give hints to Moi that he needed to make sure he was as close to Kenyatta as possible during such times,” he writes.

Mahihu also reveals that in 1977, Kenyatta was given two years to live by a team of doctors. That team included South African heart specialist Christian Barnard and other specialists from Britain.

“The team made a thorough examination of the old man and arrived at the conclusion that he was so unwell that it was not advisable to operate on him. Further – and very tellingly – the team pronounced that the old man could only be expected to stay alive for another two years, and not more. Although I have no clear evidence of that conclusion, it would in later years strike me as having been a very accurate medical assessment of Kenyatta’s chances of survival,” writes Mahihu.

At the height of his power, Mahihu had President Kenyatta’s ear. So close to the President was he that the Founding Father routinely slept in the latter’s house, where Mahihu and his wife, Miriam, had to vacate their bedroom for him.

It is through sleeping at his residence that Mahihu observed Kenyatta’s fear for crickets. One night, the insects chirped rather too loudly for Kenyatta’s liking. Kenyatta, Mahihu writes, had a deep fear for the nocturnal insects and frogs. So, Kenyatta emerged from his room in pyjamas.

“The chirping of the crickets in the compound was just too much for him to bear. To play the good host, I mobilised a whole squadron of security men to mop up the compound in search of crickets. However bemused they might have been by Kenyatta’s odd conduct, the bodyguards had no option but to obey his orders,” he writes.

The mop-up went on until almost dawn “when the crickets went quiet of their own accord”.

“Although nobody knows exactly why frogs and innocent crickets inspired so much fear in Kenyatta, at least one thing was known about his phobia for frogs. He himself intimated to those around him that he believed they were the ghosts of the colonialists whom he had vanquished during the struggle for independence,” he writes. “As for the crickets, it will probably never be known exactly what eerie image they created in Kenyatta’s psyche.”

Following Kenyatta’s death, Mahihu’s fortunes took a different turn when he was sacked over the 1pm news by Mr Moi, whom Mahihu describes as an enigmatic person “who had two or more persons in the same Moi”

“When I came to my Nairobi home for lunch one day in May 1980, my wife, Miriam, had shocking and painful news to break to me. I had just been sacked through the one o’clock Voice of Kenya radio news broadcast. I was no longer the Coast Provincial Commissioner,” he writes.

“That very morning, I had been with the President, the Vice President, the Minister in Charge of the Provincial Administration and the Director of Intelligence,” he adds. “Having served in the civil service for so long, giving the best I could to my country, the last thing I expected was to be sacked on the radio.”

Mahihu further reveals: “Incidentally, I went on record as the first senior public servant to be sacked over the 1pm Voice of Kenya radio news. After that, many other public servants suffered the same embarrassment.”

Mahihu’s influence as Coast PC has been previously written about, and some accounts have said his signature was the most important thing in securing land in the province. Some accounts say that locals and expatriates sought to curry favour with him in order to bag prime properties.

However, in the book, Mahihu portrays the Coast residents as a lethargic lot whose attitudes saw them lose out on opportunities, including owning land.

“Kenyatta fervently encouraged indigenous Kenyans to invest in any kind of business at the Coast, including tourism. Unfortunately, the local Coast people did not show any notable initiative in terms of establishing businesses,” he writes.

He lists two instances where he acquired property at the Coast: One in the early 1970s where he bought land that had coconuts in it and another initiated by Kenyatta.

He recalls a day when Kenyatta asked him, “But where is your hotel, Bwana PC?”

He writes that he replied in embarrassment, saying: “I don’t own any.”

Kenyatta then asked Mahihu who owned the plot next to the one where Mama Ngina had built the Silver Beach Hotel. Kenyatta, he writes, later convinced the Asian owner to sell a portion to Mahihu, who says he later took a bank loan and established a hotel there.

Born in 1930 in Nyeri, Mahihu attended Tumutumu Secondary School started his career as a propagandist for the colonial government at the height of the Mau Mau war. He would be the one making pronouncements to fighters on a loudspeaker.

“As the Mau Mau war intensified, my job as an information officer became more demanding. It now involved accompanying government soldiers right up to the battlefield,” he writes.

During one fierce exchange near Karatina in 1954, he writes, “I could see that the Mau Mau were outflanked. It was the appropriate time for me to make the usual call to them to surrender, or die”.

Numerously in the book, Mahihu denies accusations that he oppressed Africans.

“In later years it became a popular pastime to refer to colonial civil servants as collaborators. It remains a fact, however, that many Africans who had received a modicum of education ended up in the colonial administration, in one role or the other. None of my detractors named anyone whom I had tortured, as was alleged,” he writes.

“At no time did I engage in any malicious activities against my people. Nor did I torture any freedom fighter, as later came to be claimed in some quarters. None of my detractors named anyone whom I had tortured,” he adds.

He, however, does not deny that some of the actions of the colonial government were excessive, for instance the burning of houses.

When he was a District Officer in Molo under the colonial government, overseeing the screening of locals to ascertain who had taken a fresh Mau Mau oath, he came to have his first meeting with Kenyatta in 1948 through Pio Gama Pinto and Achieng Oneko.

What followed was a lifelong friendship between Mahihu and Kenyatta. After Kenya gained independence, Mahihu and many others were retained in the provincial administration.

It is through his closeness with Kenyatta that Mahihu got to witness the final moments of Mzee. He received a call at about 2am on August 22, 1978 from Dr Joe Wasunna, who was based at the Coast General Hospital.

“Dr Wasunna had been called by the nurse on duty at State House, and who kept a night vigil on Kenyatta,” he writes.

Mahihu called his personal doctor, Joe Pinto, to head to State House. When they arrived, Dr Pinto was there, as was Dr Wasunna — who had headed straight to Kenyatta’s bedroom.

“On entering the room, we found Dr Pinto asking for an oxygen cylinder. As happens in some of the worst moments in our lives, small things will go wrong. That is exactly what happened at that time. I was shocked out of my wits when I heard the nurse telling Dr Pinto that the oxygen cylinder in the room was empty,” he writes.

“At that point, Dr Pinto advised that we should rush to Mombasa’s Aga Khan Hospital for oxygen. Already, Dr Wasunna had placed Kenyatta down on the carpet. He knelt next to him and was trying hard to resuscitate him. Also in the room at that time was Mama Ngina and the State House nurse. We left them watching Dr Wasunna as he tried to save the life of the President, and rushed to Aga Khan Hospital,” adds Mahihu.

They rushed back to find the doctors staring at Kenyatta. Dr Wasunna, recalls Mahihu, was “in great shock and was helpless”.

He asked Dr Pinto three times to explain what was wrong, and that is when the doctor said Kenyatta had died.

“At that point Mama Ngina, who had been standing silently in the room anxiously observing others, suddenly screamed. It was a wild, uncontrolled scream that awakened her children in their rooms. They rushed to their father’s bedroom. So, we found ourselves there – the doctors, the two nurses, Mama Ngina and now three young children, helplessly surrounding Mzee’s dead body,” writes Mahihu. “It was anywhere between 3.30am and 4am. For a long time, nobody talked at all.”

Mahihu had the two doctors present write notes confirming Kenyatta’s death. Dr Pinto said in part: “I found Dr Wasunna resuscitating the President. I then took over. The attempts failed. We pronounced him dead at about 3.30am.”

Dr Wasunna’s note said in part: “I put the patient on the floor to facilitate external cardiac massage, which I started immediately. Oxygen was kept running.”

Another doctor, Eric Mngola, arrived and confirmed the findings of his two colleagues. It was Mahihu who asked them to put it in writing.

By 1pm that day, the news of Kenyatta’s death had been announced on the radio.

Thus, Mahihu’s choice to inform Moi of Kenyatta’s death thwarted the anti-Moi conspirators’ machinations and changed Kenya’s history.