Premium

Telling the Pope’s final story: A designer’s risk that redefined a nation’s front page

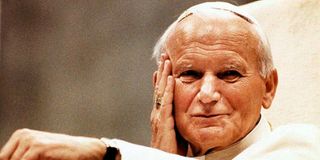

Pope John Paul II who died on April 2, 2005.

What you need to know:

- The last time the world felt such a collective loss was on April 2, 2005, when Pope John Paul II passed away.

- When the story of news design is written in this region, I hope future generations will trace part of that evolution back to this moment.

The passing of Pope Francis rekindles powerful memories — not only of my Catholic upbringing but also of a defining chapter in my media career.

Today marks another solemn moment for the global Catholic community and, by extension, the world. A spiritual leader has departed — one whose humility, charisma, and moral clarity shaped the conscience of nations.

The last time the world felt such a collective loss was on April 2, 2005, when Pope John Paul II passed away. His death transcended religious lines.

Though I was Catholic and naturally connected to him as my spiritual leader, Pope John Paul II was revered across denominations and continents.

He embodied dignity, compassion, and consistency. He was, for many of us, the only pope we had ever known.

But this story is not only about my faith — it’s also about my craft.

At the time of his death, I was serving as a lead designer in one of the region’s major media houses. I remember that day vividly. The newsroom was electric. The weight of the moment was not lost on anyone. I knew instantly that this would be one of the most important front pages I would ever help create. We weren’t just telling a story — we were capturing a historic moment for the world.

We followed every detail from the Vatican — every prayer, procession, and visiting dignitary. The newsroom was tense, alert, and collaborative. But as the days passed, it became clear that we had exhausted all the strongest images available to the public. The photos had begun to repeat themselves across media outlets. We needed to go beyond the obvious. We needed something that could evoke the weight of the loss — visually, symbolically, and powerfully.

The challenge? At the time, our editorial policy was rigid: no photo manipulation of any kind, not even for artistic effect. “A photo should go as it is,” we were told. The concern, of course, was credibility — any hint of visual tampering could erode public trust. I understood this, but I also believed that creativity and integrity were not mutually exclusive.

That’s when an idea struck me. I knew it wouldn’t pass editorial scrutiny on our flagship paper, so I decided to propose it on Taifa Leo, our Kiswahili-language newspaper. My boss wasn’t closely involved in its design, which gave me the opportunity to experiment. It was a calculated risk.

We crafted a concept — carefully, respectfully — one that blended visual symbolism with editorial integrity. We sent it to press without flagging it for managerial review. I knew we were crossing a line. But I also knew, deep down, that it was the right thing to do.

Taifa Leo's front page cover of April 8, 2005 with the story of the death of Pope John Paul II.

The next morning, my phone wouldn’t stop ringing. At first, I hesitated to pick up, expecting reprimand. Then a senior editor from the flagship paper walked over to my desk. He looked at me and said, “Congratulations on that powerful page.” He continued: “Our main edition looked like a joke next to it.”

I was stunned.

Soon after, a Director — someone who rarely spoke directly to staff — sought me out. At that time, the organisation’s annual report was being finalised.

A senior manager called to request that Taifa Leo’s front page on Pope John Paul II be included as one of the most outstanding design achievements of the year. It was a moment I’ll never forget.

That day taught me something timeless: sometimes, the boldest ideas aren’t immediately understood — especially by those in authority. If you always wait for permission, you may never execute your most meaningful work. Vision doesn’t always arrive with consensus. Sometimes it requires courage.

Yes, I risked my job by breaking the rules. But that risk became a turning point not only in my career, but also in the evolution of editorial design.

Today, satire, symbolism, and visual storytelling are accepted — even expected — in serious journalism, as long as they remain rooted in truth and do not infringe on dignity or privacy.

As we speak, that front page — bearing my byline — is still displayed on the walls of one of the largest media houses in East and Central Africa, 20 years later. When the story of news design is written in this region, especially in the realm of graphics and visual journalism, I hope future generations will trace part of that evolution back to this moment — when design dared to feel, and to say something that words alone could not.

A great leader had fallen. But in telling his story, I discovered the full weight of mine.

Edward Mwasi is Media Industry Strategy and Innovation Consultant, CBIT