Daily Nation journalist James Ngugi (Ngugi wa Thiong’o) with President Jomo Kenyatta and Vice President Jaramogi Odinga at Ichaweri in Gatundu in 1964.

Before rising to international fame, the late Kenyan novelist Ngugi wa Thiong’o began his career as a journalist, writing under the name James Ngugi for the Daily Nation.

He was among the first journalists hired to contribute regular columns, and his series, As I See It with James Ngugi, offers valuable insight into the development of his early political and literary thought.

Ngugi was a great admirer of Jomo Kenyatta, his ‘Black Moses’ in the Weep, Not Child. In the early writing, his thoughts and those of Kenyatta seemed to rhyme: “In his recent message to the nation, the Prime Minister, Jomo Kenyatta, said that having fought for independence to free ourselves from foreign rule, we had to go a stage further and liberate ‘our minds and souls from foreign ideas and thoughts.’" Ngugi was in full approval of this.

It seems that in the early days of his career, Ngugi was very much a man of his time: a young African thinker caught between cultural pride and the pressures of colonial modernity.

His early journalism reflects a voice shaped by missionary schooling and the hopeful nationalism of a Kenya on the brink of independence. But it also shows his unease with some traditional African practices, which he saw as obstacles to progress.

“Let us take the circumcision of women. This custom could be defended in the traditional society. In had a useful function not only as a means of educating but also by serving as a cohesive force in the social structure of the tribe. But now the custom has completely outlived its purpose,” Ngugi wrote in a 1962 article.

At the heart of his argument was a plea for “selective cultural nationalism.” For Ngugi, Africa’s past wasn’t something to be blindly embraced and warned against clinging to traditions that had lost their place in a changing world. Africa, he argued, needed to look forward, not backward.

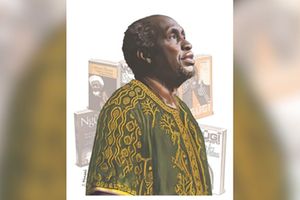

January 12, 1978: Professor Ngugi wa Thiong’o (Left) the Chairman of the Literature Department at the University of Nairobi is detained under the Public Security Act. Kenya Gazette issue number 48 details his detention and signed by the Permanent Secretary in the Home Affairs Ministry Mr Samuel Kung’u. Prof Ngugi, author of the popular book Petals of Blood was picked by police in the early hours of December 31 from his home in Limuru. Police searched his home and took away more than 100 books. He went into exile in the United States upon his release.

We catch Ngugi at a crossroads: proud of his heritage, wary of its limits, and still placing his faith in the modern nation-state as Africa’s path forward. It’s a portrait of a writer in transition—before Mau Mau trauma radicalised him, before imprisonment hardened him, before exile redefined him. A writer still searching for Africa’s future in the shadows of its past.

Ngugi’s political thinking in 1962 is interesting. In an article titled “How Much Rope Should Opponents Be Given?” he warns both camps — government and opposition — of the perils of clinging to colonial mentalities in a new era.

His central concern: the infant Kenyan State could just as easily choke itself in fear of dissent or be sabotaged by reckless opposition.

At the heart of Ngugi’s argument is a critique of post-independence governments across Africa, which, he notes, often react to criticism with paranoia and suppression.

He cites the example of Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, who blurred the line between party and State, silencing dissent in the name of national unity.

For Ngugi, this kind of authoritarianism masked as patriotism was a dangerous mirage. He cautioned Kenya’s emerging Kanu party — not yet fully in power but already flexing its muscles — against treating opposition as treason, and criticism as sabotage.

In another 1964 article, Ngugi begins with a sharp assertion that political independence is merely the beginning—not the end—of freedom.

Echoing the message of Prime Minister Jomo Kenyatta, he emphasizes that “ridding ourselves of foreign rule means only a start.” This is a crucial starting point in Ngugi’s thought that independence without mental and cultural liberation remains hollow.

His analysis reveals a critical understanding that colonialism left behind psychological residues—what he terms the “colonial mentality”—even after political structures are dismantled.

Power struggle

Another of Ngugi’s concerns was on the plight of workers in a disjointed labour movement. In an article titled “What About the Workers?”, argued that the power struggle and ideological wrangling between rival trade union factions, Tom Mboya’s Kenya Federation of Labour (KFL) and its breakaway rival, the unregistered Kenya Federation of Progressive Trade Unions (KFPTU), led by Dennis Akumu, Ochola Mak’Anyengo, and Walter Ottenyo, would hurt the workers.

At the heart of Ngugi’s argument was a clear and principled conviction: when labour leaders are divided, it is the ordinary worker who suffers most.

While acknowledging that slogans like “unity is strength” may have lost their rhetorical freshness, he insists that their truth remains unshaken. His critique was both practical and moral: divided unions not only dilute the power of collective bargaining, but also rob workers of the one instrument that could give them leverage in a new nation-state still negotiating its social and economic identity.

He questions whether the division is truly driven by principle — such as Mak’Anyengo’s stated opposition to KFL’s affiliation with the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions — or whether it is ultimately a struggle over control and ego.

“Kenya workers cannot but wonder how a split labour movement can bring about the Pan-Africa ideal. If charity begins at home, unity should begin there too. Kenya trade union leaders must come together and thrash out their differences,” he writes.

The question that Ngugi asked was if Kenya’s workers could not find common cause, how can African labour movements hope to achieve the broader Pan-African ideal?

He warned that leaders fail to unify and act in the workers’ best interests, a reckoning will come. He predicted that disillusioned workers, left without effective representation, would turn on their leaders and demand accountability. The betrayal of labour, in his view, was not just a political blunder but a moral failure with deep social consequences.

Ngugi wrote several articles on education. In the April 21, 1963, article titled “Mboya is right – Education is Investment”, Ngugi endorses Tom Mboya’s view that education must be regarded as an investment rather than merely a service.

He argues that for a postcolonial nation like Kenya, education should not be geared toward maintaining colonial hierarchies but toward developing the skills and consciousness necessary for self-rule and national regeneration.

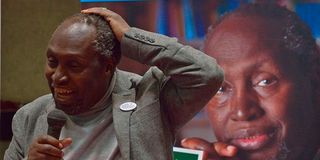

Ngugi wa Thiong'o addresses fans on June 13, 2015 in Nairobi during a book signing event to celebrate the golden jubilee of his first book 'Weep Not, Child'.

His phrase—“we must produce men and women who will not only fit into society, but who will rejuvenate that society”—echoes his lifelong belief that education should enable critical thinking, cultural confidence, and structural transformation.

Ngugi also offered a scathing critique of colonial education, which he argued bred inferiority complexes and dependency. He described the colonially educated elite as mentally colonised—ashamed of their own culture and over-reliant on Western models. He wrote:

“It produced a whole group of people with a colonial mentality whose two facets were an inferiority complex... and an extreme dependency.”

The articles reflect Ngugi’s early grappling with psychological colonialism, a theme that he would later expand into a full critique in his book “Decolonising the Mind” and later works. Already in these early writings, we see the roots of his conviction that decolonisation must begin in the mind and language, and that education is central to this struggle.

Ngugi also critiques Makerere’s elitism, the lack of African teachers, and the over-reliance on foreign expertise. This feeds to his later decision to abandon English in favour of writing in Gikuyu and his advocacy for people-centred education rooted in local languages, histories, and struggles.

He therefore called for the Africanisation of the education systems and posed the question: “How long can we continue entrusting our system of education to people, who, despite the quality of their teaching, are nevertheless products of a different social and political set -up?”

The reliance on expatriate teachers, Ngugi warned, left the minds of young Kenyans vulnerable to unconscious prejudice and subtle ideological infiltration. “The old missionary theory of education, that teaching was a calling, almost religious, should be discarded now. The trouble is that the theory apparently is still staunchly upheld.”

On literature, Ngugi was controversial from the start. While appraising the role of East African Literature Bureau, he warns that focusing too heavily on school-based literature may restrict creativity.

His argument was that literature that is written mainly for school use can become dull and focused only on teaching, instead of being creative or thought-provoking. Good literature, he argued, should also speak to adult lives, including their struggles, politics, and real-world issues.

He challenged EALB to “take more positive steps in seeking out rare manuscripts that would not normally be accepted by big commercial firms.”

That would include “collection of tribal folklore and preserving this in printed form.” Finally he says that the success of the publishing firm “will be judged on the amount of lasting literature which it has helped both to stimulate and to preserve.”

In his 1964 article on women and development, Ngugi affirmed that Kenya’s development was incomplete without the full inclusion of women.

The late Ngugi wa Thiong'o

He emphasized the “wide scope” for African women, calling them to lead in community initiatives, education, and self-help. The call to action was rooted in the post-independence national reconstruction project, which Ngugi consistently argued must be inclusive and people-driven.

In the article, Ngugi exposed the irony of patriarchal systems which framed women as too weak to govern but strong enough for physical toil.

“In the past, man's tacit assumption of woman's inferiority made him assign to her the role of producing children and providing unskilled labour on the land. Paradoxically, she was seemed too weak to take part in the manly tasks of governing and administering although deemed strong enough to be the hewer of wood and the carrier of water.”

In retrospect, As I See It was not merely a newspaper column—it was a chronicle of a young writer searching for Kenya’s future in the debris of its colonial past.

[email protected] @johnkamau1