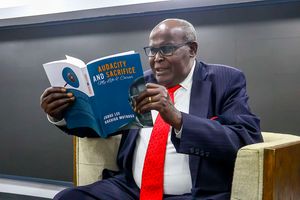

A portrait of Nyandarua MP Josiah Mwangi Kariuki, popularly known as JM Kariuki.

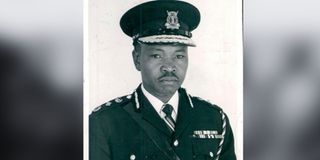

JM Kariuki always believed Ben Gethi to be a trusted confidant, and a bosom friend in the treacherous corridors of power. At no time did he believe anyone could dare touch him. He walked around without bodyguards and was a night owl. He had friends in the intelligence and counted senior police officers as his friends. They drank together and whiled away evenings at the casino, gambling.

The late politician Josiah Mwangi (JM) Kariuki.

Yet, fate would soon unveil a cruel betrayal. In the final days before his disappearance, Gethi—the General Service Unit Commandant—trailed JM like a shadow. His presence was no longer one of camaraderie but of calculated surveillance as JM’s popularity reached crescendo.

While Gethi kept a watchful eye on JM, step by step, another sinister force was at play. Ignatius Nderi, the Director of the Criminal Investigation Department, worked tirelessly behind the scenes, weaving a tale to implicate JM in the 1975 Nairobi bomb blasts planted by an organisation calling itself Masikini Liberation Organisation.

Former CID director Ignatius Nderi.

The wave of bombings revealed that the Kenyatta (Jomo) succession struggle was getting deadly — a matter of life and death.

Hour to silence him

Believing, or purporting, that JM was the man behind Maskini Liberation Organisation, the hour to silence JM had arrived — the final act of treachery. Were the bombings the work of the intelligence and had they been planned with JM’s assassination in mind? That question has never been answered, and no one was arrested. Finally, it was Gethi, the so-called friend, who would deliver JM into the hands of death, luring him from the Hilton Hotel to the interrogation room— “where the murderers were waiting,” as the Parliamentary Select Committee chaired by Elijah Mwangale later described with chilling finality.

Hours before JM was taken from Hilton, on March 2, 1975, police reservist Patrick Shaw cleared the street of beggars and taxi drivers around the hotel in order to reduce the number of witnesses.

Then the cover-up began.

On Monday, March 3, 1975, two Maasai elders, Musaite ole Tunda and Meja ole Nchoki, stumbled upon JM’s body, which had been dumped the previous night. Between 11am and noon, they reported their discovery at Ngong Police Station, stating that they had found the body of a well-dressed man at Oloshoibor. However, instead of immediate action, the officers at the station told them to leave and return at 2 pm.

The Occurrence Book later recorded the report at 2:25pm, raising questions about the delay. Meanwhile, Inspector Kinyanjui inexplicably took the only government-issued Land Rover and left for Magadi, claiming he needed to hand over the Magadi Police Station to Inspector Ndegwa. The Parliamentary Select Committee that investigated the murder noted that “either Inspector Kinyanjui or Inspector Ndegwa, or both, suspecting or somehow knowing the body to be that of JM, decided to leave for Magadi, leaving Inspector Waga, Kinyanjui’s deputy, to go through the motions of investigating the dead body.”

No fingerprints taken

At the crime scene, Inspector Waga, who was responsible for collecting the body, neither took fingerprints nor photographed the site. Although JM’s body was discovered in the morning, it was not collected until 3:30pm and was only taken to the mortuary at 5:25pm, where it was registered as an “unknown adult male.” Amid the chaos caused by the March 1 bomb blast, JM could have easily been mistaken for one of its victims. It would remain concealed at the mortuary until March 11.

The following day, after the body was collected, Inspector Waga sent a signal to the OCPD at Kajiado that he had collected the body of an “adult African male” and taken it to the mortuary. No details were included. On March 6, Inspector Waga instructed a Constable Gitau to go and take the fingerprints of the body recovered three days earlier. The police claimed that these were sent to the Criminal Records Office (CRO) for identification, and the report said the fingerprints were “untraced.” As a result, according to the police, the identity of the body was still unknown. It emerged later that the fingerprints had not been taken for identification to the Ministry of Labour, the custodian of fingerprints, until March 12, when they were positively identified as belonging to JM.

All this time, JM’s “friend” Ben Gethi had done little to trace him. “It is possible that if the body of JM had not been discovered by JM’s widows and Members of Parliament, the police had no intention of facilitating the identification of the body and it would have been buried as unclaimed and as unidentified,” the Select Committee report concluded.

Former police commissioner Ben Gethi.

It was intriguing how casually the police handled JM's disappearance. Although it was evident that he had been murdered using firearms, by March 12, the only report in JM’s file contained statements from two Maasai elders—Ole Tunda and Ole Nchoki.

At the CID headquarters, Ignatius Nderi, who had facilitated the release of convicted fraudster Peter Kinyanjui, alias Mark Twist, to track JM, destroyed the tape recording of Kinyanjui’s call to JM, which was meant to link him to the bombings. Mark Twist also followed JM to the Ngong races.

From March 2, when JM was murdered, the police appeared to be stalling, hoping that in the chaos of numerous unidentified bodies at the City Mortuary, JM’s body would be buried as unidentified.

“There were indications that attempts were being made to get JM’s body passed off as that of a Luo gangster because of the missing lower teeth,” noted the Select Committee.

By Thursday, March 6, JM’s wives reached out to Starehe Member of Parliament Charles Rubia for help and publicly disclosed that JM was missing. The family had previously visited the mortuary but had not identified any of the unknown bodies. That afternoon, Mr Rubia sought a government statement on JM’s whereabouts. Speculation arose that he might have been detained without trial.

However, neither the Kenya Broadcasting Corporation nor any print media reported on Rubia’s parliamentary inquiry.

On Friday, March 7, 1975, the Daily Nation published a special edition emblazoned with the chilling headline: “JM Kariuki is Missing”.

‘JM alive in Zambia’

The report quoted Justus ole Tipis from the Office of the President, who tersely stated: “All we know is that his wife informed the police that her husband has been missing since March 2."

That same day, intelligence operatives orchestrated a deliberate misdirection. Nation Editor-in-Chief George Githii and News Editor Michael Kabugua were fed a false trail—an elaborate deception suggesting that JM was alive and well in Zambia, lodged at the Intercontinental Hotel. The Saturday Nation perpetuated the cover-up, running the sensational banner: “JM in Zambia”.

Yet across the nation, anxiety festered. The specter of Tom Mboya’s assassination, just six years prior, loomed ominously over the unfolding mystery.

Meanwhile, at the Criminal Investigations Department (CID) headquarters, Director Ignatius Nderi sought to feign ignorance, instructing Nairobi CID chief Kimani to open a missing person’s file. When later pressed by the Parliamentary Select Committee, Nderi conceded that his inquiries had been superficial—he simply did not believe anything serious had befallen JM.

However, the events at CID that Friday painted a different picture. Gemstone dealer Pius Kibathi was picked up for questioning. Oddly, though JM’s body had not yet been officially located, Kibathi was interrogated about his murder—a term that had not yet entered public discourse. One of his interrogators bluntly demanded: “Do you know who murdered JM?” His response implicated Ignatius Nderi and the shadowy, fearsome figure of Patrick Shaw, both of whom had been at the Hilton Hotel the night JM disappeared.

Pius Kibathi.

For this revelation, Kibathi paid dearly. He was tortured and incarcerated at Kamiti Maximum Security Prison for over a month, from March 7 to April 9, 1975. No charges were ever brought against him. When he later testified before the committee, his words suggested that the CID had always known JM was dead. Yet Nderi refused to have Kibathi’s statement examined—least of all by the parliamentary investigators.

Widow gets tip off

While Parliament was being told that JM was merely "missing," the CID’s actions betrayed a different reality.

On March 8 and 9, officers combed through JM’s home—not in search of the man himself, but of his vehicle, scouring it for bomb residue. Their focus on his car rather than his person hinted at foreknowledge of his fate.

Then, on March 11, an anonymous caller tipped off the widow Terry Kariuki, stating that JM’s body was at City Mortuary. At 5 pm that day, Terry, accompanied by MPs, rushed to confirm the claim—only to be barred from entry. For a tense hour, they were obstructed, until an assistant commissioner of police finally relented at 6 pm, permitting access. The next day, March 12, the grim truth broke: JM was dead.

It was Ignatius Nderi who handpicked the "investigators" charged with probing the murder. The Parliamentary Select Committee later decried this move, concluding that the team had been assembled not to uncover the truth, but to suppress it.

Key witnesses were intimidated. At the Hilton, all persons who could have witnessed JM leaving the Hotel were rounded up.

The witnesses were picked up and held in custody, ostensibly, for questioning. A taxi driver named Githinji, who had seen Gethi walking out of the hotel with JM, was detained and interrogated for four days. Meanwhile, when JM’s wristwatch surfaced at the Makongeni Police Lines, a logical investigative lead was ignored. Instead of questioning the 39 officers residing there, Superintendent Singh Sokhi instructed Corporal Kisaka—whose son had found the watch—to remain silent about the discovery. Nderi later concocted a feeble attempt at misdirection, alleging that Kibathi himself had planted the watch at Makongeni. Yet, when pressed for answers, Nderi dismissed all inquiries, claiming—without evidence—that Kibathi had fled to either Uganda or Tanzania after his release from Kamiti.

Efforts to scrutinise the CID’s investigation were systematically obstructed. Initially, Nderi had agreed to provide MPs access to the investigative files. However, Police Commissioner Bernard Hinga overruled him. When Hinga was summoned before Parliament, he arrived flanked by the formidable criminal lawyer Byron Georgiadis, prepared to stonewall. Hinga proposed a subcommittee to examine the exhibits, but when members arrived at CID headquarters, Nderi merely showed them the files—without allowing them to read a single page. When pressed further, Hinga outright refused to order Nderi to provide full access.

“The conclusion of the Committee,” the final report stated, “is that Hinga and Nderi had something they wished to hide or that they were afraid of the Committee discovering the perfunctory nature of the CID investigations.”

Other police officers also refused to cooperate with the inquiry. For instance, Erastus Mungai, the Rift Valley police boss, and in whose jurisdiction the body was found was contemptuous of the Parliamentary Committee and spoke with “hostility and rudeness.” While recommendations were made to investigate Pius Kibathi, Peter Njau, Peter Kimani, and Patrick Shaw, all of them walked free. Others implicated—including Nakuru Mayor Mburu Gichua, Ol Kejuado Councillor John Mutung’u, District Commissioner Stanley Thuo, National Youth Service Deputy Director Waruhiu Itote, Evans Ngugi, and Mbiyu Koinange’s bodyguard, a Mr. Karanja—likewise evaded scrutiny.

Former Cabinet minister Mbiyu Koinange. Photo/FILE

In the final act of obfuscation, before the Select Committee’s report was published, President Jomo Kenyatta himself intervened. Under his direct orders, the names of two powerful figures—Mbiyu Koinange and Wanyoike Thungu, a State House operative and bodyguard—were expunged from the record. Koinange had been invited, as Minister of State, to discuss how to secure the cooperation of various arms of government. He never appeared nor sent an apology.

Thus, the truth about JM Kariuki’s assassination was buried—not unlike the man himself, a casualty of state-sponsored silence and impunity.

The Parliamentary Select Committee later concluded that “investigations carried out by the police have neither been thorough nor genuine.” It concluded that the police know who the culprits actually are but are unwilling to proceed against them.”

Tomorrow: How JM’s assassination shaped Kenyatta regime

[email protected] @johnkamau1

Also read:

PART I: The day JM Kariuki vanished