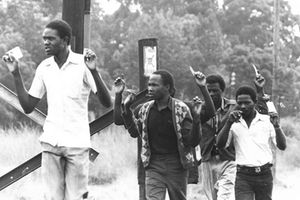

Some of the of the hundreds of Mau Mau suspects who were rounded up in Nairobi after the Lari massacre of March 26, 1953.

My father’s young brother, Uncle Tom Mbotela, loved politics a lot. He was among the team that fought for Kenya’s Independence in 1940s and 50s. Unlike my father who was a bit reserved, Uncle Tom was an outgoing man who interacted with people across all social classes.

He had friends in high places in government as well as in the villages. He was a talented multi-linguist. He spoke English, Kiswahili, Kamba and Kikuyu with perfect ease. He was quick to begin a conversation with anybody on any topic. He used to talk a lot. Many people in our family said I took after him because I am equally talkative.

Uncle Tom, as we fondly called him at home, was born in 1912. He received his education at home, just like his other siblings. By the virtue of growing up in Kamuthanga, he became very fluent in the Kamba language, to the extent that many people who interacted with him believed he was a Kamba.

He served as a teacher in Machakos for a short period. He then moved to Nairobi and joined Baraza newspaper as a journalist. He wrote articles about the future of Africa and Africans.

While working as a journalist, Uncle Tom quickly gravitated towards politics. He was at home in the raucous domain of politics. He knew how to speak in public, lead a demonstration, demand an explanation from adversaries, give a warning, woo supporters, threaten an opponent, initiate a political narrative designed for a certain end, address a roadside gathering, and whip up emotions, among other traits that are common with politicians and politics.

In a file picture taken in October 1952 soldiers guard suspected Mau Mau fighters behind barbed wire in the Kikuyu reserve at the time of the Mau Mau uprising against British colonial rule in Kenya. PHOTO | AFP

Uncle Tom was the opposite of my father who was too straightforward to fit in what he termed “the dirty game of politics.” Father did not talk a lot, and he never knew how to please someone for the sake of it. He was too honest and spoke what was in his mind. He never knew how to play around with ‘nice’ words. He hated politics.

Uncle Tom was a good orator. When the politics of Independence was boiling up, he threw himself into the deep end. He became the Secretary General of Kenya African Union (KAU) in 1950 at the time when Jomo Kenyatta was the Chairman.

KAU was formed to push for Kenya’s Independence. However, it was banned in 1952 when its leaders, the famous Kapenguria Six, were arrested and detained for allegedly organising the Mau Mau rebel movement. They included Jomo Kenyatta, Paul Ngei, Bildad Kaggia, Fred Kubai, Achieng’ Oneko and Kung’u Karumba. The then Governor, Sir Evelyn Baring, declared a state of emergency at the same time.

The six were charged in a Kapenguria court, over 400 kilometres northwest of Nairobi, for jointly managing a proscribed society that had allegedly conspired to murder all white residents of Kenya. Their case was heard by Judge Ransley Thacker and they were represented by lawyer Denis Pritt who was friendly to Kenya’s independent leaders. To honour him after Independence, a road in Nairobi near State House was named after him.

This lawyer, a British leftist who later became a Professor of Law in Ghana, dismissed the charges against the six Kenyans terming them “the weakest case made against any man in the history of the British Empire.” All the same, Kenyatta and his team were jailed for seven years.

Kapenguria was chosen for the trial for it was considered ‘safe’ because the Mau Mau movement was growing stronger and deadlier in Central Kenya, Nairobi and other parts of the country. The lethal Mau Mau, it was believed by the white colonial government, could not access this remote place (West-Pokot) and rescue the six. The area lacked basic amenities. The road leading there was almost non-existent and there was no railway system either.

Meanwhile, the fighting continued. The British soldiers killed thousands of Mau Mau fighters, and this made the rebellion worse. Very many white farmers in Nakuru, Kiambu, Molo, Uasin Gishu, among other areas, were attacked by the Mau Mau. During this emergency period, there was a lot of tension across the country.

The British used some loyalist Africans, better known as Home Guards, to fight or provide intelligence on the Mau Mau. On their part, the Mau Mau intensified their activities and recruited more members and made them take an oath of allegiance. Many Africans who refused to take the oath were murdered.

Suspected Mau Mau sympathisers are surrounded by armed askaris who, according to Tim Symonds, were employed by the colonial government to assist white officers track down and arrest Mau Mau fighters in the dense Mt Kenya Forest. PHOTO/FILE

Though he was a fiery politician who detested colonial rule, Uncle Tom was against the culture of oath-taking that was championed by a section of the African leaders at the time. The oath aimed at causing Africans to disengage totally from dealing with the colonialists and to be ready to attack the whites whenever one encountered them.

The oath ceremony included passing under the arch, sipping a distasteful mixture of symbolic elements and uttering sacred vows. The oath was carefully thought out and so strongly worded that once a person had taken it; there would be little risk of reporting the facts to authorities.

The oath was a discreet document whose contents were hardly known. Furthermore, many people never spoke about it for fear of Mau Mau’s reprisals. However, as a journalist, I kept asking around quietly and conducting research to get to know the contents of this oath that my uncle rejected, and which ended up costing his life. Later, I discovered its wording...

**

This oath was considered totally binding, even when it was forced upon the taker. Those who took it could be relied on to find and kill the colonialists and African “traitors” who supported or sympathised with the coloniser.

British Secretary of State for the Colonies, James Griffiths (left), talks to Jomo Kenyatta and a Kikuyu elder in Kiambu in May 1951. Griffiths had come to Kenya to obtain the views of community leaders on constitutional changes.

Uncle Tom did not buy into this idea. Being a very vocal man who said what he meant and meant what he said without fear. He made it clear to fellow politicians who supported Mau Mau that he did not support the taking of the oath and forcing others to take it against their wishes. He also spoke against Mau Mau’s acts of violence and lawlessness. This created tension between him and the other pro-Mau Mau leaders.

Also Read: The fading legacy of Jomo Kenyatta

This difference of opinion between him and the other KAU party officials forced him to resign from the party. The party’s ideology had changed and he did not see the role he could play in it. He knew very well that forcing others to take an oath that they did not understand was a violation of their rights as human beings. He also believed in using non-violent means in agitating for Independence.

Politics is a very interesting game. Once you differ slightly with your ‘team-mates’ you always find yourself welcome in the opposite team. This is what was perceived to have happened with Uncle Tom.

Governor Evelyn Baring, whose position was equivalent to the country’s President, began to take a keen interest in Uncle Tom ‘for being a reasonable and level-headed’ politician. Governor Baring described Tom as a leader who did not blindly oppose the government for the sake of it. Consequently, he had Uncle Tom nominated as a Councillor in Nairobi. The colonial government saw him as a voice of reason. On the contrary, Uncle Tom was seen as a sell out by the diehard Mau Mau adherents. They hated him and marked him for elimination.

One evening in November 1952, Uncle Tom attended a dinner party in Nairobi that was hosted by Governor Baring. The event took place at a venue along Jogoo Road, then known as Donholm Road. The road was named after the Donholm Dairy Farm that began in the area today known as Donholm Estate by James Kerr Watson, one of the colonial white settler farmers in Kenya. This farm stretched from today’s Makadara area through Buruburu Estate to the present day Donholm Estate in Nairobi.

In a file picture taken in April 1953 captured suspected Mau Mau fighters are marched towards Githunguri court in Kenya at the time of the Mau Mau uprising against British colonial rule. Britain has agreed to compensate Kenyans tortured during the Mau Mau uprising against colonial rule in the 1950s, Foreign Secretary William Hague said June 6, 2013 AFP

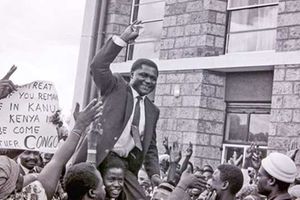

That night as Uncle Tom made his way from the dinner party to his house in Kaloleni at 11pm, he was accosted by unknown men wielding crude weapons. They hacked him to death. His lifeless body was discovered by the roadside ditch in the morning. It had multiple deep cuts. . Accusing fingers were pointed at the Mau Mau. Uncle Tom’s death sparked riots in Nairobi.

A newspaper article published on November 29, 1952, under the headline ‘Mau Mau Murder in Nairobi” read: An African gang believed to be Mau Mau terrorists, hacked to pieces Tom Mbotela, an African nominated member of Nairobi City Council. Mbotela’s mutilated body was found lying near the African Stadium (now City stadium) in Nairobi.

Another popular city councillor called Ambrose Ofafa was also killed the following day by suspected Mau Mau adherents. He too was opposed to the idea of taking the oath. There is an estate in Nairobi named Ofafa after this Mau Mau victim.

An abrupt death in the family can be very shocking and traumatising. I was about 12 years old when Uncle Tom was murdered. I still harbour the pain of his death. His murder touched everyone in our family. He was a loving and outgoing man. He was at ease and friendly to everyone; young and old, rich and poor, educated and non-educated. He attracted friends like a magnet.

Back at home, his easy-going nature had made him a darling of his brothers and sisters, and the extended family. His nephews and nieces always longed to visit his house.

The country’s last colonial governor Sir Malcolm MacDonald, right, during a meeting. FILE PHOTO |

My grandfather, Juma, was still alive when his 40-year-old son was killed. The old man, then 72, wrote a very long and emotional account of events that happened before and after Uncle Tom’s killing:

“Tom was a likable person. He was sought by Europeans, Asians and Africans on various matters. When he joined the City Council, he found himself in the company of Europeans who did not know where to turn to in the confusion of Kenya’s politics. They sought Tom’s advice . This made him the object of suspicion by some KAU and Mau Mau adherents.

“It was rumoured that he had been approached by the whites to co-operate with them in opposition to Africans. But Tom was loyal to KAU and Kenyatta’s leadership, even after he resigned from KAU leadership. The situation with Mau Mau was getting worse. The government arrested Kenyatta. Things deteriorated rapidly. Many people came out openly saying they wanted Independence.

“During those days, I was living in Nairobi. As a result of my work with the Censorship Department of the Army, during the war years, I was given a job with the Special Branch of the Kenya Police for translation of Swahili and vernacular newspapers into English. Because of that job, I learned a lot about what was happening in the country. I learned that there were plans to kill Tom. This was naturally sad news for me and my wife. So, we told Tom not to say much in politics and live a quieter life.

“An attempt had earlier been made to assassinate him in 1950, alongside Muchohi Gikonyo, a moderate civic leader. However, the assassination failed. Gikonyo was wounded by a shot in the hand, and Tom escaped unhurt. After that, Tom was given a government bodyguard.

Leonard Mambo Mbotela’s book, ‘Je, Huu Ni Uungwana.’

“However, there was one Kamau who used to travel a lot with Tom. Tom said he was a good friend but my wife and I never thought so. We thought he was a suspicious person and we told Tom as much. We lived on the edge all the time after Tom broke off from KAU’s leadership. Eventually, when the news of his death came in, I fainted.”

Uncle Tom was buried in Langata Cemetery, Nairobi. After his murder, my grandfather was advised to move to Mombasa and work from there. It was said that the Mau Mau were not done yet and that they had threatened to kill all the members of the Mbotela family.

My grandfather was too devastated to continue working in Nairobi. He lived in fear and eventually, opted to retire a year later to his home in Mombasa. Being a religious man as one of the pioneer African missionaries, he went back to what he knew best. He became active in church as a member of ACK (Anglican) Emmanuel, Freretown Church. While there, he also served as an advisor at the Mombasa District Council.

My grandfather concludes his narration about Uncle Tom thus:

“When (Jomo) Kenyatta became President, I once met him and he told me that I had paid a price as high as anyone. That meant much to me. Tom’s monument is the Nairobi’s Mbotela Estate which is named after him. In a sense, that was a good move by the colonial government because Tom had devoted many years working for African housing and welfare in Nairobi.”

My grandfather was a very forgiving man. He never held any grudge against anybody. After this incident, he declared that he had forgiven the killers of Tom and that he was proud of what Tom had done and had intended to do for Kenyans.

Uncle Tom’s death was a big blow to my father. I saw him mourn his brother bitterly and for a very long time. I could see and feel the pain among my relatives. As a result of this gruesome murder, my father began to despise politics. He rarely attended political rallies or never followed political events.

He preferred to talk about education, religion, business, social life, among other things. Whenever he encountered people discussing politics or gathering around a transistor radio listening to political news, he would dismiss such preoccupation and aver “that is what killed my brother Tom.”

Following Uncle Tom’s death, the colonial government named Mbotela Estate, in Nairobi’s Eastlands (along present Jogoo road), after him.

Read the first installment - Leonard Mambo Mbotela’s account of Tom Mboya’s death and 1969 Kisumu bloodbath - HERE

Read the second installment - Leonard Mambo Mbotela: Day I was caught in the middle of 1982 attempted coup - HERE

Read the third installment - Leonard Mambo Mbotela - Day I was summoned to military court over 1982 attempted coup - HERE

© Leonard Mambo Mbotela