Mandera County Referral Hospital, where only three out of five dialysis machines are operational.

Imagine a healthcare system where expired drugs line shelves, critical equipment lies broken, and hospitals are severely understaffed. Twelve years after the advent of devolution, this is the grim reality in parts of Kenya.

A recent report by the Senate Health Committee following an oversight mission to Mandera, Wajir, and Marsabit counties lays bare systemic failures that are putting millions of lives at risk.

The report, tabled on May 1, paints a dire picture of healthcare under county governments, raising serious concerns over governance, accountability, and service delivery in the devolved health system.

Led by Uasin Gishu Senator Jackson Mandago, the committee found a litany of issues: drug stock-outs, expired medicines, broken infrastructure, absent personnel, and poor financial transparency.

“We found expired drugs dumped in open fields and others stored in disused toilets due to the lack of incinerators,” said Bungoma Senator Wakoli Wafula.

“Healthcare is not just about buildings. It’s about personnel, systems, and accountability. What we found was a sector in deep crisis,” added Senator Mandago.

Mandera County Referral Hospital, where only three out of five dialysis machines are operational.

In Mandera, the senators toured Mandera Teaching and Referral Hospital, Elwak Sub-County Hospital, and Khadija Dispensary. They discovered obsolete equipment and malfunctioning machines. At Mandera’s main referral hospital, only three of five dialysis machines were operational. CEO Adan Okash admitted the hospital was overwhelmed: “We need at least ten machines to meet demand. Currently, we are falling short.”

Staffing was another major concern. In some cases, untrained personnel were dispensing medication. “Some facilities have no pharmacists,” noted Senator Mariam Omar. At Khadija, expired drugs lined the shelves, and a clinical officer, Abdihaziz Mustafa, admitted to dispensing medicine without formal pharmacy training.

In Elwak, staff cited lack of equipment and transport. Public health nurse Mohammed Adan appealed for more vehicles to support outreach and emergency services.

In Marsabit, the committee visited the county referral hospital where rising patient numbers - particularly at the cancer clinic - have outpaced capacity. The clinic now receives about 20 patients a month, double the previous figure, but lacks diagnostic equipment. As a result, tests are sent to Nairobi, causing delays.

Kisii Senator Richard Onyonka questioned these delays, and hospital administrators admitted they were unable to perform specialised tests locally.

The hospital’s infrastructure was also in disrepair - non-functioning plumbing, filthy wheelchairs, and unkempt grounds. Expired drugs and sanitiser were still in use, and hazardous waste was dumped in abandoned toilets or open fields.

The committee also questioned the fate of Sh200 million allocated during the Covid-19 response for an ICU unit. Marsabit Governor Mohamud Mohamed Ali said only Sh18 million was used for ICU work and insisted the unit was operational.

Dialysis machines at Wajir County Teaching and Referral Hospital.

In Wajir, the team visited Manyatta TB Centre and Wajir Teaching and Referral Hospital. Staff raised concerns over safety and the absence of a modern laboratory. “We lack personal protective equipment and a functional lab,” said the facility’s officer in charge. The facility also lacked mosquito nets, proper laundry systems, and digital record-keeping in the maternity ward.

Senator Abbas Sheikh Mohamed raised concerns about delayed reimbursements under the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) and Facility Improvement Fund (FIF), noting that service delivery remained crippled despite funding.

Governor Ahmed Abdullahi acknowledged the challenges and pledged reforms, including provision of mosquito nets, appointment of a substantive hospital CEO, and completion of a World Bank-funded Sh600 million dumpsite by September.

This comes barely a month after another Senate investigation uncovered deplorable conditions in county-run hospitals across the country.

The Senate County Public Investments and Special Funds Committee, chaired by Vihiga Senator Godfrey Osotsi, reported underfunded Level 4 and 5 hospitals, stock-outs of essential supplies, and faulty billing systems leading to revenue losses.

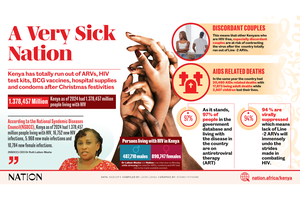

Read: Anatomy of a sick nation

In Nyeri, Karatina Sub-County Hospital was flagged for lacking critical services expected of a Level 4 facility. Mt Kenya Sub-County Hospital was grossly understaffed, with only 21 community health nurses instead of the required 75, and just two medical officers instead of 12.

In Kwale, Kinango Sub-County Hospital was short of 44 healthcare workers, including specialists. Staff there said they were overwhelmed, demoralised, and fatigued due to the high patient load and limited support.

The situation was similarly dire in Bomet, where Longisa County Referral Hospital was also cited for poor conditions and inadequate staffing.