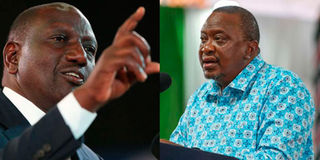

President William Ruto (left) and his former boss, Uhuru Kenyatta.

“We are between a rock and a hard place.”

That is how Education Cabinet Secretary (CS) Julius Ogamba described the status of funding learning in the country on Thursday, when he appeared before the National Assembly Education Committee.

He was honest and candid.

“We need to discuss how we can fund the education sector in the country. Persistent underfunding affects the quality of education. It is a live problem,” Mr Ogamba said.

Education Cabinet Secretary Julius Migos Ogamba.

An analysis of data from 2018, when the underfunding started affecting school operations, paints a gloomy picture of the future of provision of free basic education as envisaged by the third President Mwai Kibaki.

It is also a constitutional right since 2010 for the government to provide free and compulsory basic education to learners. Secondary schools are worst hit with over Sh64 billion in unremitted capitation funds and the trend appears to be worsening every year.

When President Mwai Kibaki won the 2002 presidential election, he wasted no time in executing one of his most popular campaign promises — free primary education (FPE).

Also Read: End of Kibaki's free education

In January 2003, millions of children trooped to public primary schools across Kenya, many attending school for the first time but armed with a burning desire to learn. It was a transformative moment for Kenya’s education sector and a turning point for countless families.

Despite challenges such as overcrowded classrooms and insufficient learning materials, the policy opened doors for millions of children, many of them now in the popular Gen-Z age group, that is giving the powers-that-be, sleepless nights.

Mr Kibaki's bold move set Kenya on a new path.

Former President the late Mwai Kibaki.

His successor, President Uhuru Kenyatta (2013 to 2022), expanded the vision by increasing the capitation for the free day secondary education (FDSE), and introduced the 100 per cent transition from primary to secondary school.

Enrolment soared, especially after the government raised capitation per learner and pumped billions into school infrastructure, teacher recruitment and curriculum reform.

This trend, however, appears to be in reverse gear under President William Ruto, with the future of free education remaining uncertain. Although no official policy has changed free primary or secondary schooling, budgetary data shows a quiet but unmistakable roll-back of government support — most notably through reduced capitation per learner.

The Kenya Kwanza administration appears to be undoing, through financial neglect, what previous regimes built through deliberate policy.

Budget trends

The story of Kenya’s education funding is best told through its budget trends. During Kibaki’s administration (2002–2012), FPE was the crown jewel, and education spending was treated as a national priority.

The momentum continued under Mr Kenyatta, with consistent increases in secondary education capitation from Sh10,265 in 2015 to Sh22,244 by 2018. Mr Kenyatta’s tenure saw secondary school enrolment rise from 1.3 million to nearly 3.6 million by the time he retired in 2022.

The examination waiver was introduced by President Uhuru Kenyatta in 2015 for all public school learners and was extended to private school learners in 2017.

According to data from the Controller of Budget, budgetary allocations for secondary education climbed for the year ending June 2018 from Sh58.5 billion, climbing to Sh62.8 billion in the year ending June 2019 up to Sh71.9 billion in the year ending June 2022.

However, the financial year ending June 2024, the funding had dropped to Sh67.88 billion – a Sh24.91 billion decline from the previous year when it stood at Sh92.79 billion. Meanwhile, capitation per student has stagnated at Sh22,244, despite rising inflation and enrolment pressures.

In primary education, a similar script plays out. Capitation stood at Sh20.1 billion in 2017-2018 but dipped to Sh18.47 billion in 2020 -2021 and slightly rebounded to Sh21.12 billion in 2022 under Mr Kenyatta.

Under Dr Ruto’s administration, it has again dropped – to Sh19.01 billion in 2023/24.

President William Ruto has ordered an audit of compliance with safety standards and regulations in all schools.

In the 2025/2026 Budget set for reading next week, what has played out is the case of robbing Peter to pay Paul, with legislators raiding the capitation for learners in public schools to finance examination administration and invigilation.

The National Assembly Budget Appropriations Committee has proposed an allocation of Sh5.9 billion for examination administration and invigilation, that has been sourced from the recurrent capitation for junior school (Sh2 billion), secondary school (Sh3 billion) and primary School (Sh900 million).

Bigger issue

This erosion of capitation is not just a financial issue—it’s a matter of access and equity.

Also Read: The evolution of Kenya’s education system

In the 1990s, under then President Moi, school fees and other levies excluded many children from poor households.

Literacy levels stagnated, dropout rates were high, and regional inequalities were pronounced. Free education under Kibaki and Kenyatta regimes changed that trajectory, but those gains are now at risk.

Students walk on the streets of Nakuru city.

Parents are again being asked to pay for “hidden costs” such as remedial classes, development fees, and school maintenance—expenses that are increasingly difficult to meet for low-income families. Transition rates from primary to secondary school are showing signs of decline.

Enrolment in secondary schools has dropped to 3.2 million, despite the country previously nearing 100 per cent transition.

Widening gap

Though the government runs support programmes like the Elimu Scholarship Programme under the Kenya Secondary Education Quality Improvement Project and the Kenya Primary Education Equity in Learning Programme, their reach is limited. Many deserving children are left out, and regional disparities are widening.

For instance, of the 95,016 applicants in the 2023 cohort, only 14,426 were successful.

Worth remembering is that under Mr Kenyatta, education was not just about access — it was about quality and equality.

His administration increased capitation, rolled out the Competency-Based Curriculum and recruited over 120,000 teachers. These efforts were based on the understanding that education was both a social right and an economic imperative.

Now, as Dr Ruto administration shifts focus to other policy areas, education funding seems to be taking a back seat.

The Presidential Working Party on Education Reforms recommended a capitation of Sh22,257 for senior schools—barely above the current level—and the proposal remains on the shelf.

The Kenya Kwanza government has not abolished free education, but it may not need to. By quietly cutting or stagnating funding while costs rise, it is effectively reintroducing barriers to access.