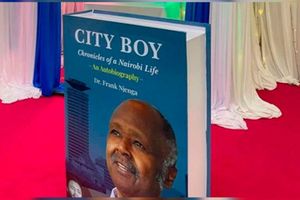

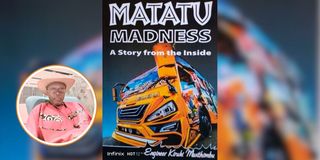

Author Kiruki Mwithimbu (inset) and the cover page of his book Matatu Madness: A Story From the Inside.

The title of this new book by prolific writer Kiruki Mwithimbu, Matatu Madness: A Story From the Inside, is quite inviting, and focuses on the highly negative image of this vital public transport industry.

However, there is much more that the author, a seasoned engineer, reveals about the development of the entire Public Service Vehicle (PSV) industry.

And Eng Mwithimbu could not have chosen a better person to write the foreword. Prof Gerrishon Ikiara, a former Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Transport and Communications, is a top consultant on economic and policy development. According to him, this book provides a major and unique understanding of the evolution, growth and contribution of the matatu industry to national development.

No better person could have brought out the intricacies than this engineer, who has for many years played a pivotal role in the transport business. Kiruki is a manager with EasyCoach bus company, which is one of the most efficiently managed PSV enterprises.

But as Prof Ikiara points out, the title, Matatu Madness, aptly captures the early phase of the industry’s evolution, when “the dominant driver behaviour was unashamedly crazy!” His conclusion: “This book is a major source of information for those interested in understanding the dynamics of Kenya’s PSV industry”.

There are interesting anecdotes in this book, which traces the founding of major transport firms such as Kenya Bus Services. In 1934, KBS started operations in Nairobi with 13 buses on 12 routes. The fleet had grown to 50 by 1952.

By independence in 1963, KBS had 100 buses, all maintained and controlled from their Eastleigh depot. The mode of operation was tailored on the London commuter buses, including the double decker buses introduced in 1957.

Founding President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta’s contribution to the birth of the matatu industry remains intriguing. When the key players tried to lock out these struggling transporters, Mzee Kenyatta told off the Kenya Bus Owners Association (KBOA), whose officials visited him at his Ichaweri home in Gatundu, in the then Kiambu District in March 1973.

He sealed the dominance of the bus owners by declaring: “Those who feel operating buses is not suitable for them, go sell them and buy matatus. Everyone has to eat!”

And with this final remark, Matatu Madness was born.

Matatu is, of course, the word used to describe the motor vehicles used for public passenger transport. It developed out of the informal vehicle transport enterprise; indeed, the pirate taxis that charged 30 cents for any journey and played hide and seek with traffic police.

The matatus, the writer explains, “first started as taxis with point-to-point contracted runs, and later started stopping at the KBS-designated stages while calling out for passengers and charging them a flat rate of 30 cents — mang’otore matatu. Before long, the bus stages would be inundated with chants of matatu, matatu, matatu – that became the signature call of the informal PSV service, ma.ta.tu.

Between 1967-1970, the regular matatu was an old Ford Zephyr operating between Jericho Estate in the Eastlands and the Country Bus Station near the city centre, whose youthful drivers had one eye on the road and the other on the roadside looking out for the loathed traffic police officer.

By 1980, the matatu industry had “matured into a very noisy mob populated by a rainbow of models. The makanga (conductor/tout) became the feature of infamy”.

By 1995, there were about 6,500 matatus in Nairobi in comparison to 3,500 in 1992.

But talk of success going into one’s head — the PSV industry later became rogue and then Transport minister John Michuki would rise and slay the dragon.

The introduction of the “Michuki Rules” was a government attempt to rein in excesses in the PSV industry. He sought to restore sanity to an industry that had become a big success and also crazy. The raft of new regulations addressed etiquette, crew discipline, route allocation and road safety.

This stripped the manyanga of its romantic elegance. As the writer graphically puts it, “once operators complied with the new regulations, Nairobi matatus started looking like chickens without plumage — all plain and without character”.

The minister’s fiat strangled a dynamic industry of fine artists, graphic designers, electricians and sound engineers, who were compelled to peddle their talents elsewhere.

This continued until 2017, when President Uhuru Kenyatta repealed the tough regulations during election campaigns to win favour with youth, and manyanga-mania returned with a vengeance. The city came alive with a kaleidoscope of colours restoring past glory.

But road accidents are the curse of the PSV industry. The causes include human error, mechanical failure, speeding, and driving under the influence of alcohol. The consequences are loss of lives, injuries, psychological trauma, and economic burdens and damage to vehicles. Accidents strain healthcare systems.

The writer gives great insights into the contributions of key players in the development of the PSV industry. They include General Motors, Kenya Coach Industries, Auto Spring Manufacturers at Athi River and Associated Motors that was born in 1964 in the lakeside town of Kisumu.

And this is not just a story about the matatu industry, Eng Mwithimbu has his own tale tucked in it. He was privileged to have witnessed it from his vantage point as a production engineer at Auto Spring Manufacturers, a service engineer in General Motors and a service manager in Associated Motors.

Long before Michuki came up with his draconian rules to tame the matatu madness, one company, Kensilver Express, had excelled with virtues that were queer by the standards of the day.

Its vehicles never exceeded the 80KPH speed limit set by the Transport Licensing Board (TLB). Disciplined drivers wore neat navy-blue uniforms, there was no overloading, and the buses never stopped for on-road passengers. The buses would leave even with only three passengers on board and were regularly serviced and inspected before every trip.

If Kensilver lit the fuse to bring sanity to the matatu world, then EasyCoach was the explosion. Some 16 years after the founding of Kensilver Express, another daring entrepreneur birthed a dream of taming matatu madness. Azym Dossa had been the financial controller of Akamba Bus Service, an iconic brand.

Following the death in 2000 of Akamba boss Sherali Hassanali Methoo, Dossa, a quiet, calculating sage, set out to create his own brand. It took three years to fashion his marque branded EasyCoach. When the first buses appeared, the simple combination of three colours – black, white and red – was like a breath of fresh air in an industry that was choking with barmy artistry. The initial fleet was 11 Fuso buses built in an elegant coach design with a touch of class.

A consummate workaholic, Dossa built his company on six pillars that made EasyCoach stand out like a giraffe in the savannah grassland: Safety, Security, Reliability, Punctuality, Comfort and Innovation.

The buses were quite a sensation on the western Kenya routes, especially when they converged on the Seguton Mall in Nakuru Town for a well-deserved toilet break.

Seguton happened to be the late President Daniel arap Moi’s property, hence the torrid rumour that this was his retirement package. But the speculation served EasyCoach well as it rode on the goodwill until the post-election chaos of 2008, when six buses were burnt to ashes in Kericho. With goodwill from the government and empathy from customers, the firm soon bounced back and has remained unchallenged.

The author joined EasyCoach Ltd in April 2004, four months after it started operations. He now manages over 100 buses covering 1.4 million kilometres per month.

Says he: “Our fleet registers very few accidents – and we’re grateful to God for this. We’ve built in strong road safety and driver management policies that differentiate us from others. In a nutshell, there are three main causes of road accidents – the Man, the Machine and the Road.”

In many ways, the core structure and modus operandi of the PSV industry bears the DNA of the Kenya Bus Service that was introduced in Nairobi in 1932. The matatu trait took its own tangent and defined the omnipresent craze that Kenyans know today as matatu madness. This is going to be with us for a long, long time.

Says the author: “The matatu has been despised, disparaged and ridiculed, but every morning and evening, Kenyans make a beeline to partake of its services without which the country would grind to a halt.”

Kiruki is an alumnus of Meru and Kagumo high schools. He is also the author of "Living on the Edge" and "A Saint to Behold". He is a farmer under the blogging banner, Mkulima No. 2, and a passionate cyclist. [email protected] (Tel. 0725834839)