Premium

Close call in Mogadishu: A journalist’s timely memoir

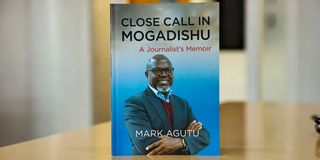

The book cover of Close Call in Mogadishu: A Journalist's Memoir by Mark Agutu.

What you need to know:

- Somalia has not seen peace since President Mohamed Siad Barre was toppled in 1991.

- New book outlines historical events that led up to the transitional government’s homecoming.

Book: Close Call in Mogadishu: A Journalist’s Memoir

Author: Mark Agutu

Pages: 100

Somalia is rising from the debris of decades of civil war and political turmoil and asserting itself again on the world stage.

A few days ago, a newly confident Somalia - in a diplomatic dispute related to a port deal between Ethiopia and the breakaway region of Somaliland - threatened to expel Ethiopian troops if that agreement was not scrapped.

About 10,000 Ethiopian soldiers are stationed in various regions of Somalia, some 3,000 of them as part of an African Union peacekeeping mission called ATMIS that is fighting the terrorist group Al-Shabaab, which still controls large parts of Somalia.

In the same week, Somalia, which has not seen peace since President Mohamed Siad Barre was toppled in 1991, won a non-permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council, the first time it will hold the position since the 1970s.

The UNSC decides how the world body responds to conflicts, and Somalia’s experience will influence those decisions.

That is a far cry from the situation 20 years ago. Things were much more fluid then, and nothing was guaranteed.

In 2007, the Somalia Transitional Federal Government – based in Nairobi, elected months earlier following a peace conference and led by a man named Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed - moved to Mogadishu.

But clashes between warring factions had almost scuttled that relocation months earlier. President Ahmed had sent a fact-finding mission to Mogadishu, led by Prime Minister Ali Gedi.

Their assignment was to assess conditions in the capital and see whether the newly elected government could operate from there.

On May 4, 2005, Gedi was addressing thousands of Somalis in the Mogadishu National Stadium on the new government’s planned agenda when … boom! An explosion rattled the stadium, killing 15 people and injuring dozens.

Gedi was spared, though it could not be determined whether the terrorists who had planted the bomb were targeting him.

But that was Mogadishu being Mogadishu – dangerous, lawless, chaotic, fluid, uncertain.

This unnerving event, the history that preceded it, the aftermath and snippets of life in the Somali capital are the subjects of Mark Agutu’s new book, Close Call in Mogadishu: A Journalist’s Memoir.

Agutu was a court reporter for the Daily Nation but had been asked by his news editor to be part of a group of journalists to accompany leaders of Somalia’s new government on their first trip to Mogadishu.

As someone conversant with Somalia’s recent history, Agutu was acutely aware of what he was in for, as this would be his first trip to that war-scarred country.

He describes his fears about his safety, some triggered by his consumption of popular culture, but also cites his excitement.

In a brisk, readable narrative style, Agutu outlines historical events that led up to the transitional government’s homecoming.

The negotiations in Nairobi and elsewhere between warring parties were complicated and hadn’t been easy, and were frequently interrupted by clashes back in Somalia.

It wasn’t easy either for some of the countries that worked to help Somalia regain stability. The most notable episode came in October 1993 and involved American special forces, who had come to Mogadishu to arrest warlord Mohamed Aidid and his lieutenants.

In the shootout that ensued, a US chopper was shot down and dozens of American soldiers and hundreds of Somalis were killed, becoming the inspiration for the non-fiction book Black Hawk Down and the 2001 war film of the same name.

Kenya was hit too, though not on the same scale. Months earlier, in July, the Americans had bombed Aidid’s headquarters with helicopters. Outraged mobs confronted international journalists who had gone to the scene of the attack and killed four, including two Kenyans.

The devastating events of 1993 were a major setback for Somalia and the countries working to help it, and the author outlines the peace efforts the international community made in the years that followed. Kenya was among the countries deeply involved in these efforts.

Agutu also provides glimpses of one iconic building in Mogadishu that still stood as a symbol of not just power but the resilience of the Somali people.

It is Villa Somalia, the complex overlooking the Indian Ocean that started life in 1936 as the residence of governors in Italian Somaliland.

For the warlords, it was a status symbol, and many battles were fought among various factions for control of it in the years that followed the overthrow of Siad Barre.

Though carrying bullet and mortar marks and is no longer glitzy, Agutu writes, it carries its frame and features “stoically like a proud soldier bearing the scars of war”.

There was another curious symbol of Somali resilience that Agutu writes about. In tight security, journalists accompany PM Gedi to a Catholic mission on the outskirts of Mogadishu led by an elderly nun that serves deprived Somalis.

There is a church, a school, a health centre and residences - an island of Christian endeavour in a sea of Islam.

The nuns, Agutu writes, “doubled up as teachers, farmers, medical workers and social workers, spearheading mercy missions for the benefit of the local population”.

The dedication. The sacrifice. The patience. The audacity.

Writing about the resilience of the Somali people, Agutu says that the dynamics that attended the negotiations that led to the creation of the transitional government “might have served to portray Somalis as intolerant people, blinded by unfettered loyalty to clan interests at the expense of other considerations for nation building”.

But in the short time he spent in Mogadishu, he found ordinary Somalis “a friendly, welcoming lot and even their language is interesting to learn.”

This timely book is not just about a week in the working life of a journalist and the sacrifices they often make at great risk to their own lives to bring us important stories about our world.

It is also about interesting and consequential episodes from the recent history of Somalia, a country scarred by war and struggling to get back on its feet.