A women-led mangrove conservation project in Gazi, Kenya, is transforming carbon credits into tangible community gains—like piped water, school bursaries, and medical supplies.

When Ms Mwatime Amadi walks along the white-sand Gazi Women Mangrove Boardwalk in Kwale County, she's not just showing tourists a beautiful ecosystem—she's showcasing a pioneering carbon credit project that has transformed her community's relationship with nature while positioning Kenya at the forefront of global climate finance innovation.

"The carbon credit project has significantly improved our lives," explains Amadi, a tour guide at the boardwalk. "When we sell carbon credits, the proceeds fund numerous community projects: purchasing school books for our children, establishing a water project, supporting the Madrassa, and buying equipment and medicine for our dispensary."

The Gazi community's innovative approach has become a model for Kenya's growing engagement with carbon markets—a sector that gained unprecedented momentum following the breakthrough agreement on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement at recent climate negotiations.

The Mikoko Pamoja initiative began in 2014 when community members stopped harvesting mangrove trees—prized for their strong building wood—and instead began selling carbon credits from their conservation efforts.

The Boardwalk, an ecotourism project for the women of Gazi community, was established earlier in 2006 as a token of appreciation from the City Council of Belgium and The Earth Watch team, facilitated by the Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI).

Dr James Kairu, a mangrove management specialist at KMFRI, explains the remarkable environmental value these coastal forests represent.

"Mangroves play a crucial role in the blue carbon ecosystem, as they sequester substantial amounts of carbon," says Kairu, who has worked with mangroves for over 20 years. "While terrestrial forests with root depths of up to 30 centimetres store about 150 tonnes per hectare, mangroves with roots reaching six metres deep can store between 1,500 and 3,000 tonnes per hectare."

This extraordinary carbon storage capacity makes the community's 117-hectare mangrove forest a valuable asset in the fight against climate change. The project sells approximately 3,000 tonnes of carbon credits annually, generating up to $60,000 (approximately Sh7-8 million) depending on market conditions.

"Because we produce high-quality carbon, the market price fluctuates between $20 and $40 per ton," Kairu notes. These premium prices reflect the multiple benefits mangrove conservation provides beyond carbon sequestration—coastal protection, fish nursery habitats, and biodiversity enhancement.

Mangroves account for only 61,000 hectares of forests nationwide, representing a mere three per cent of Kenya's gazetted forest cover. Yet their ecological value far exceeds their size. "Mangroves' value to fish, coastal protection, and the community far outweighs their size. Deforestation is the main threat to this vital ecosystem," Kairu explains.

How Local Communities Benefit

Unlike some carbon projects where benefits remain abstract, the Gazi model ensures tangible community improvements through a transparent governance structure.

"The money is deposited into the account and our coordinator for the Gazi and Makongeni communities manages the distribution," explains Amadi. "There are set percentages: Gazi receives 32 per cent, Makongeni receives its own percentage, and the rest is used for reinvestment in the mangrove forest."

The organisation conducts community meetings to determine which projects will deliver the greatest local benefit before implementation. This participatory approach ensures that conservation translates into real-world improvements.

Ms Mwanahawa Bakari, a lifelong Gazi resident and project member, witnessed the transformation firsthand.

"I always thought that mangroves grew naturally. Through educational efforts, I learned that people plant them, and that there are up to nine species. Now, we know how to walk in the water and how to plant in salty water," she says.

The carbon credit payments have dramatically improved daily life, bringing piped water that ended the need for long treks to fetch water. Community members also receive stipends for planting mangroves, and some, like Bakari, have begun growing seaweed among the mangroves for additional income.

"The sale of carbon credits has led to significant improvements. At present, a small number of students benefit from bursaries funded by these proceeds. As we have only recently begun selling, the number is still low. We are hopeful that the number of beneficiaries will increase shortly as we continue our work," says Bakari.

The success of Mikoko Pamoja comes as Kenya positions itself as a leader in Africa's carbon market development following the historic agreement on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan.

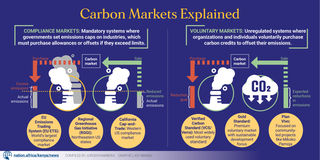

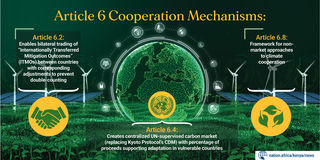

After eight years of contentious negotiations, nations finally reached consensus on the rules governing international carbon trading under Article 6, which establishes three mechanisms for countries and private entities to collaborate on emissions reductions:

Article 6.2: Allows for direct bilateral trading of carbon credits between countries through "Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes" (ITMOs)

Article 6.4: Creates a centralised UN-supervised carbon market mechanism replacing the Kyoto Protocol's Clean Development Mechanism

Article 6.8: Establishes frameworks for non-market approaches to climate cooperation

The agreement provides clarity on how to avoid double-counting emissions reductions (ensuring both buyer and seller countries don't claim the same reduction), sets standards for environmental integrity, and mandates that a percentage of proceeds from carbon trades support adaptation in vulnerable developing countries.

For Kenya, which has enacted some of Africa's most progressive climate legislation, the Article 6 agreement opens significant opportunities. The country's Climate Change Act Amendment of 2023 established a comprehensive legal framework for carbon markets, with the government aiming to capture a substantial portion of Africa's potential $82 billion annual carbon market.

Kenya recently launched a national carbon registry to track and verify emissions reductions, preparing for increased international trade. The registry will help monitor projects like Mikoko Pamoja and ensure they meet international standards for the higher-value compliance markets that Article 6 will facilitate.

"Kenya, being a signatory to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), is required to engage in regulated carbon trade through the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM)," explains Kairu. "However, because of the CDM's lengthy procedures, we in the Mikoko Pamoja project choose to use the voluntary market."

Under the new Article 6 framework, the transition from the CDM to the Article 6.4 mechanism will streamline procedures, potentially making regulated markets more accessible to community projects. Additionally, the agreement's provisions for ensuring a share of proceeds support adaptation in vulnerable countries could channel more climate finance to communities like Gazi.

The Mechanics of Carbon Credit Generation

Understanding how communities like Gazi generate sellable carbon credits reveals the blend of science and community engagement that makes these projects work.

Kairu breaks down the process: "When the mangrove trees grow, we use science to estimate its growth rate and the carbon it accumulates." Researchers measure the stored carbon by assessing the leaves, trunks, and soil down to one metre. By counting and measuring trees within a one-hectare area, they can calculate that the area stores approximately 700 tonnes of carbon.

The project follows a "deforestation avoidance strategy," preventing the community from harvesting mangroves and enabling the trade of these avoided emissions. "We are not selling in sacks," Kairu clarifies. "We measure the carbon not released and convert it according to the international carbon market."

Buyers include Napier University (UK), Free University of Belgium, Net Zero (Sweden), individuals, and conference organisers looking to offset their carbon footprints. The project operates in the voluntary carbon market, where participation is optional rather than mandated by regulations.

"If you know your company is emitting and you are conscious of the environment, you can purchase to offset your carbon imprint. For example, if you have travelled from Nairobi, we can estimate the carbon you have emitted, and you can buy an offset. Even Kenyans can now engage," says Kairu.

Despite its success, the project faces ongoing challenges. "The vast forest is guarded by only two officers, which is insufficient," says Amadi. "We urgently need at least four officers to deter interference. We have had instances of illegal logging, and arrests have been made."

Kairu acknowledges that changing deeply ingrained harvesting practices takes time. "We have been able to convince the community to live in harmony with the system. Initially, it was difficult since they thought we were coming to harvest their forest. However, the community is embracing conservation from a few individuals."

For the Gazi community, expansion of their mangrove forest beyond the current 117 hectares would mean more carbon credits to sell—and more community benefits. The Coast region is already seeing increased output, with Vanga's annual sales reaching up to 6,000 tonnes and Lamu projecting even greater potential.

Gabriel Njoroge, a University of Nairobi master's student studying mangrove carbon in biodiversity, sees immense potential for growth.

"My research has been significantly enhanced by being embedded within the community, as it provides a practical understanding of my studies. This allows me to analyse data and forecast future outcomes."

As projects scale up, governance becomes more complex.

"The benefit sharing mechanism is still an issue," Kairu notes. "We have empowered our community to manage the project. It is run by a committee elected every two years, and by keeping it in the community, we have enhanced transparency. If we were to increase the volume, we would think about how to increase the beneficiaries to include the county and national government."

Kenya's approach to developing community-based carbon projects like Mikoko Pamoja positions it as a leader in implementing the new Article 6 framework in Africa. The country's national climate action plan explicitly identifies carbon markets as a key financing mechanism for meeting its emissions reduction targets.

While many carbon market initiatives in developing countries have faced criticism for failing to deliver community benefits, Kenya's community-centred approach offers a different model. By ensuring local communities maintain decision-making power and receive tangible benefits, projects like Mikoko Pamoja demonstrate how the Article 6 mechanisms can promote both climate and development goals.

Kenya's government is now working to aggregate smaller community projects into larger programs that can more efficiently access international carbon markets under Article 6. This could help scale the Mikoko Pamoja model nationwide while maintaining community ownership.

Global Opposition to Carbon Markets

Despite the success of projects like Mikoko Pamoja, carbon markets face mounting criticism and legal challenges worldwide. Indigenous groups, environmental justice organisations, and some academics argue that carbon offsets allow polluters to continue emitting while transferring responsibility to vulnerable communities.

"Carbon markets can become a form of 'green colonialism' if not implemented properly," explains James Kairu. "We've deliberately designed Mikoko Pamoja to avoid these pitfalls by ensuring community control and transparent benefit-sharing."

Indigenous communities have been at the forefront of resistance. In Brazil, the Munduruku people filed a landmark lawsuit in 2023 against a carbon project operating on their ancestral lands without proper consent. The São Paulo Court ruled in favour of the Munduruku, invalidating carbon credits sold from the project and establishing a precedent for indigenous rights in carbon markets.

Similar conflicts have emerged across the Global South. In Uganda's Kachung Forest Reserve, local communities reported displacement and lost access to farmland after a Norwegian company established a carbon forestry project. The resulting legal challenge led to the first ruling requiring redesign of a carbon project with stronger community protections and compensation for affected villagers.

The situation in Kenya is somewhat different. While the country embraces carbon markets nationally, disputes have arisen over benefit distribution. In Lamu County, community members filed a case with Kenya's National Environmental Tribunal in 2022, arguing they were excluded from decision-making in a large-scale mangrove project. The case resulted in an order to restructure governance to ensure broader community representation – a lesson Mikoko Pamoja had already implemented.

Carbon and conservation projects face serious allegations of land grabbing and rights violations. The Northern Rangelands Trust (NRT), one of Kenya's largest conservation organisations, managing over 4.5 million hectares across 39 community conservancies, has become a flashpoint in these debates.

Indigenous pastoralist communities, particularly in northern Kenya, have accused the NRT of using conservation and carbon finance to effectively take control of ancestral lands. These communities argue that the "community conservancy" model restricts traditional grazing routes and livelihoods while carbon revenues primarily benefit external organisations rather than local people.

"The carbon market landscape in Kenya is diverse," explains Kairu when asked about these controversies. "Some projects genuinely empower communities like ours, while others have been criticised for imposing external agendas. Each project must be evaluated individually."

In 2021, pastoralist groups from Isiolo, Samburu, and Marsabit counties filed a formal complaint with NRT's international donors, alleging that carbon projects were being developed on their lands without proper consultation or consent. A subsequent investigation recommended significant reforms to NRT's governance structure and benefit-sharing mechanisms. In January this year, the court delivered a blow to NRT, issuing orders that included a permanent injunction prohibiting NRT and its partners from conducting any conservancy operations, including the recruitment and deployment of rangers, in the affected areas.

The Ogiek community's struggle represents one of the most significant land rights cases in Kenya's history. Though not directly related to carbon markets, their experience highlights the risks when conservation initiatives overlap with indigenous territories. After a decade-long legal battle, the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights ruled in 2017 that the Kenyan government had violated the Ogiek's rights by evicting them from ancestral forest lands in the name of conservation.

Despite this landmark ruling, implementation has been slow, and some Ogiek leaders have expressed concerns that emerging forest carbon projects in the Mau Forest complex could further complicate their land claims. The government's creation of a task force to implement the court's decision has been criticised as inadequate by Ogiek representatives.

These controversies underscore the critical importance of secure land tenure and community consent for ethical carbon market development. Kenya's Climate Change Act Amendment of 2023 attempts to address these issues by requiring documented community consultation and benefit-sharing agreements for all new carbon projects, but implementation challenges remain.

"At Mikoko Pamoja, we benefit from clear community rights to manage mangrove forests," notes Amadi. "Not all communities in Kenya have that security, which creates challenges for equitable carbon project development."

These controversies are reshaping carbon market regulations. The Article 6.4 Supervisory Body now requires "robust stakeholder consultations" and grievance mechanisms for all new projects. Meanwhile, major standards bodies like Verra and Gold Standard have strengthened indigenous rights protections in their certification requirements.

"We closely monitor these developments," says Kairu. "The lesson is clear – carbon projects only succeed when communities meaningfully participate in design, implementation, and benefit-sharing. At Mikoko Pamoja, local ownership has been fundamental from day one."

The Gazi Women Mangrove Boardwalk Project at Gazi in Kwale County which is helping the community by using carbon credit sales to support other beneficial projects.

As Kenya expands its carbon market ambitions under Article 6, the community governance model pioneered at Gazi offers valuable lessons for avoiding the pitfalls that have plagued carbon projects elsewhere. The women of Gazi have shown that when local communities lead conservation efforts and control the resulting benefits, carbon markets can deliver both environmental and social justice.

In the evolving landscape of global carbon markets, the women of Gazi say they have found a path that honours their traditional connection to the land while embracing new economic opportunities from conservation, ensuring their children inherit not just trees but a sustainable future.