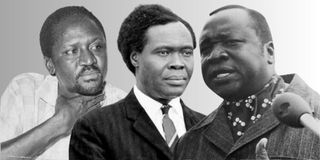

Poet Okot p’Bitek (left), Uganda's former presidents Milton Obote and Idi Amin.

When our people die, we bury them quietly, return each year with flowers and whisper their names into the wind. We do it respectfully. Solemnly. And in doing so, we miss a massive economic opportunity. The truth is that the dead have duties to the living. From their graves, they could help build a tourism economy Uganda has never dreamed of.

Consider Morocco, Africa’s top tourist destination, pulling in close to 18 million visitors annually. Yes, it has markets and medinas, but part of the magic lies underground. A recent Atlas Obscura piece highlighted a sprawling 13.5-hectare cemetery on the edge of Rabat—home to the tombs of Sufi saints and other revered figures. These sites draw pilgrims, spiritual tourists and the merely curious, adding to Morocco’s tourism boom.

Outside Africa, the business of the dead is booming. Over 600,000 people troop to Graceland every year to see the king of rock and roll Elvis Presley’s resting place in Memphis. Musician Jim Morrison’s grave in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, gets over 3.5 million visitors yearly.

Martial arts megastar Bruce Lee’s grave in Lake View Cemetery, Seattle, receives tens of thousands every year. Reggae supremo Bob Marley’s mausoleum in Nine Miles is one of Jamaica’s leading tourist attractions. Philosopher Karl Marx’s grave in Highgate Cemetery, London, marked by a large bust, is the most visited in Highgate.

The Wadi-us-Salaam cemetery in Iraq, the largest in the world, holds over six million bodies and receives millions of Shi’ite pilgrims annually. Gamal Abdel Nasser’s mausoleum in Cairo draws Arab nationalists and modern history pilgrims. Nelson Mandela’s legacy sites, especially Robben Island, attract over 300,000 visitors a year—most just to see his cell.

Kasubi Royal Tombs

Uganda? We had time to debate passionately about whether the Kasubi Royal Tombs should be rebuilt with steel or reeds. Yet we’re not short on candidates.

Kabalega lies at Mparo in Bunyoro. Milton Obote is alone in Akokoro. Yusuf Lule and Ignatius Musaazi are half-forgotten in Kololo. One of Africa’s great poets, Okot p’Bitek, is buried inconspicuously at St Philip’s Cathedral Cemetery in Lacor, Gulu. And Idi Amin—love him or loathe him—is buried in obscurity in Ruwais Cemetery, Jeddah.

The time has come to build a new kind of cemetery. A national historic cemetery that is all teched up. Let’s exhume and rebury Uganda’s past in a single, central site. Think interactive tombstones, and QR codes telling their stories—warts and all. Imagine a holographic Obote explaining UPC’s logic, Amin playing the accordion, or a digitised Okot p’Bitek reciting Song of Lawino at dusk.

Children on school trips could complete an entire history syllabus in one afternoon. Graduate school students would have enough material to begin writing their term papers. Tourists, too, would find stuff worth their money: something strange, something solemn, something memorable.

I suspect Amin would be the biggest draw. The world remains fascinated with him. His corner of the cemetery alone could pull 600,000 to 850,000 visitors annually. Obote, Lule, Kabaka Mwanga, King Kabalega and p’Bitek would bring in decent traffic too.

But we’d need to do it right. First, lock out partisan politics. A cross-sectional, credible board should determine who gets a plot in this cemetery. Otherwise, it becomes another burial ground for powerful men’s mistresses and favourite children who didn’t accomplish anything noteworthy.

If we’re honest, Uganda’s tourism still leans heavily on what God gave us—mountains, rivers, waterfalls and gorillas. Beautiful, yes. But we can’t climb to five million annual tourists on primates, the source of the Nile and elephants alone.

Iconic attractions

Look at the world’s most visited places: The Dubai Fountain, situated at the base of the Burj Khalifa and adjacent to the Dubai Mall, is one of the city’s most iconic attractions. While specific annual visitor numbers for the fountain alone aren’t public, the Dubai Mall—which provides direct access to the fountain—welcomed a record-breaking 105 million visitors in 2023 and surpassed 111 million in 2024, solidifying its status as the most visited place on Earth.

Times Square, New York, gets 50 million visitors annually. The Las Vegas Strip, 42 million. The Great Wall of China, 10 million. Disneyland in California and Paris, 16 and 10 million, respectively. The Louvre in Paris pulls in 9.6 million. The Eiffel Tower gets seven million. None of those are natural wonders. They are not gifted by nature, as we are wont to say. They’re built environments. Human-made experiences.

We can’t export waterfalls. But we can build stories around the lives and legacies of the people buried here. People with contradiction, charisma and consequence. Uganda’s forgotten cemeteries could become powerful mirrors for the living. Places where memory, education and tourism collide.

Our dead will have to rise, one last time—not to haunt us, but to hustle for us.

The author is a journalist, writer, and curator of the “Wall of Great Africans”. X@cobbo3.