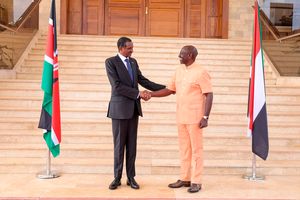

President William Ruto (left) greets President Felix Tshisekedi of the Democratic Republic of Congo in Kinshasa on November 21, 2022.

Not three months have passed since President William Ruto launched the revised Kenya Foreign Policy Manual. The document, an update on the previous guideline published in 2014, was finalised after the Ministry of Foreign and Diaspora Affairs organised extensive engagements with stakeholders and interest groups under what was dubbed the “Whole of Government and Society” approach.

It was a progressive document, which laid down broad principles and policy objectives around Kenya’s engagements with the rest of the world. It emphasised a proactive approach, which, for some of us privileged to engage the ministry on the initial draft, went some way towards advancing our foreign policy from what we used to term the ‘wait-and-see’ approach.

An element of the manual restated Kenya’s reputation in peace and security issues, pointing out involvement in peacekeeping efforts and mediation of regional, continental and global conflicts. But as we have seen in the last few months, it is one thing to have comprehensive and well-thought-out policies on paper, and quite another to actually live by them.

Roadside declarations

Kenya’s foreign policy right now is a shambles, mostly because President Ruto has adopted what can only be described as policy by roadside declarations. While we tout our well-established credentials as peacebuilders and conflict mediators, we are engaging in risky misadventures that fuel conflict and bloodshed, placing us at odds with other countries in the region.

One year before the launch of the Foreign policy document, for instance, the Democratic Republic of Congo recalled its ambassador in protest at Kenya allowing leaders of the M23 rebel group and other smaller militias, which roam and pillage the eastern part of the country, to announce the formation of a ‘Congo River Alliance’ from Nairobi.

Since then, DRC President Félix Tshisekedi has refused to accept the credentials of President Ruto’s nominee for the vacant ambassador’s office in Kinshasa.

Recently when Ruto, as chair of the East African Community, summoned an emergency meeting of the regional body’s heads of state to discuss escalating conflict in eastern DRC, including capture of key regional capital, Goma, President Tshisekedi boycotted the talks.

Another country that has reason to be angry with Kenya is Sudan. The past few weeks have seen a constellation of militia groups, led by the infamous Rapid Support Forces (RSF), allowed to use Nairobi as the platform for the launch of a rebel government-in-exile. President Ruto has previously angered Sudan President Abdel-Fattah Al-Burhan after rolling out the red carpet for RSF leader Mohammad Hamdan Dagalo Mousa, also known as Hemedti, who is blamed for a wave of atrocities perpetrated by his bloodthirsty militia.

The Cabinet Secretary for Foreign and Diaspora Affairs, Musalia Mudavadi, who also serves as Prime Cabinet Secretary, has offered the ludicrous responses that allowing rebel groups to set up base in Kenya was compatible with peace and mediation efforts. Nothing could be further from the truth, as our foreign misadventures in both Sudan and DRC brazenly flout and undermine all peace efforts by the East African Community, the Intergovernmental Authority of Development (Igad), the African Union and the United Nations.

The ministry has tried to justify DRC and Sudan rebel groups apparently being given succour and comfort in Nairobi as simply an example of the rights and liberties that reign in the country, including freedom of speech, association, expression and the freedom of political organisation.

That could sound like a compelling argument, but for the fact that this government has been guilty of aiding and abetting illegal abductions and renditions of personalities from countries that have sought refuge in Kenya. Ugandan opposition leader Kiiza Besigye is the most prominent opposition leader kidnapped in Nairobi, obviously at the behest of President Yoweri Museveni, and sent to face trial at home before a rigged judicial machinery.

We have also had incidents of others fleeing persecution in countries as varied as Ethiopia and Turkey seized in Kenya and spirited away to be jailed in their home countries. The kind of hypocrisy put forward beggars belief.

The foreign meddling probably played a significant role in scuttling Kenyan candidate Raila Odinga’s bid for the African Union Commission chairmanship. More seriously, it has left seasoned Foreign ministry hands scratching their heads in disbelief at the disastrous policies apparently driven from the State House.

Career diplomats have been sidelined, and outnumbered, as clueless political appointees, in continuation of a trend that started under the first Jubilee regime of President Uhuru Kenyatta and DP Ruto, now hold sway in key embassies and the ministry headquarters. The Foreign Policy Manual is now not worth the paper on which it is printed.

[email protected]; @MachariaGaitho