Peter Kimani and Ngugi wa Thiong'o at Amherst College in Massachusetts, United States in 2018.

This is the story that I dreaded writing, even though I knew I had to someday. And I knew he would have written my own story had I departed ahead of him. For the story of my life in writing is intricately woven with that of Prof Ngugi wa Thiong’o, the pioneering Kenyan author and one of Africa’s brightest stars, who has died at the age of 87.

I first encountered Ngugi in 1986, as a Form One student, through his seminal novel, Weep Not, Child, a tender tale of Njoroge and Mwihaki, two youngsters who are caught in the vortex of violence, in the shadow of Kenya’s war of liberation in 1950s, as their parents are caught on the opposite sides of the struggle.

Having spent my formative years in a village in Gatundu, on the fringe of Nairobi, which was ringed by large coffee estates, the vestiges of the colonial economy—the scars of the past were manifestly present: Villagers murmured who among them had sold out, ngaati, as they were called, a corruption of “homeguards,” and the patriots who fled to the forest to fight the colonialists.

And of course we had the spectre of Jomo Kenyatta, our founding President and local MP, coursing through the village to his abode in Ichaweri. He, too, sprung from the pages of Ngugi’s fiction, conflating fact into fiction.

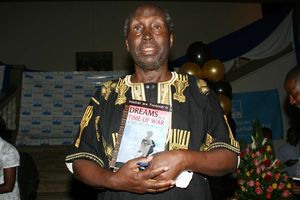

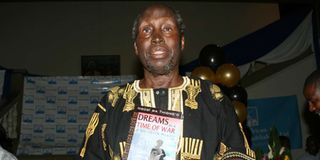

Celebrated Kenyan author and scholar Prof Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

Ngugi’s novel was not on the school curriculum; in fact, in that very year, 1986, his effigies were burnt in city streets by a rabidly paranoid State. All these events left my 15-year-old mind discombobulated: what I wanted to read wasn’t outlawed, but it was authored by an outlaw!

“The Kenyan authorities have on a few occasions complained about Ngugi’s presence,” a leaked diplomatic communique from London, dated October 1984, squeaked. “We have no evidence that he’s actively working against the Kenyan government… He is outspoken in his public criticism of the Kenyan government, but he is a dissident intellectual rather than a politician, and certainly he is no terrorist.”

The political nuances of his work were yet to be revealed to me; neither was I aware of the miseducation that we were being subjected to, as the first cohort of 8-4-4, even though I silently questioned the value of constructing a mud and wattle hut without a single nail for a school project in Nairobi.

This maze of confusion mirrored Njoroge, the protagonist in Weep Not, Child, and his mother’s enduring faith that in the white man’s education lay a potential roadmap to a better future. I wasn’t the studious type, so that analogy didn’t quite appeal to me. What gripped my attention was the possibility that I could write my own story.

This clarity and purpose came from a blurb on the cover of Weep Not, Child and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, which I read in that same year. Both books announced that the two authors had served as journalists before becoming novelists. I, too, would become a journalist and a novelist!

This was the beginning of my self-education, devouring any of Ngugi’s texts that came my way. I literally followed in his path, cutting my teeth as a journalist on the Daily Nation in the early 1990s, as he had 30 years before me. When I published my first novel, Before The Rooster Crows, in 2002, I mailed a copy to him at the University of California, Irvine, where he served as distinguished professor of English and Comparative Literature.

Prof Ngugi wa Thiong'o holds a copy of his autobiography titled Dreams in a Time of War. It was launched in Nairobi on August 19, 2010.

The following year, in December 2003, I made a pilgrimage to meet my hero, the beginning of a life-long friendship. I recall being struck by his diminutive stature, appropriating the Gikuyu proverb, ngumo ndiigana mwene, which means fame seldom matches its owner.

A luncheon meant to last an hour stretched into a five-hour catch up and a detour to his home. He had opened his life to me. From then on, Ngugi would feature prominently in my life’s milestones, making efforts to visit whenever I was in the Northern hemisphere. Hardly a week went by without a phone call.

“It’s so frustrating watching things from afar,” he often lamented. What he desperately wanted was not the large conversations on politics—he invented the term “paper parties” to describe the special purpose vehicles that litter our landscape, bereft of ideological clarity. What he wanted was the touch of the everyday, the expressions of the common man in the streets.

A long-held, but grossly flawed misconception of Ngugi is that he was a political demagogue. This is a fictive construct that sought to undermine and simplify his complex world view, but also his commitment to democratise his country, and with his words, empower the masses.

“When I write about peasants,” he narrated to me, “I think of my mother, Wanjiku. She was always working, toiling on her farm.”

Above all, his friendship came first. In 2015, when he was invited to the State House by President Uhuru Kenyatta, he came to my house first to bless my last-born son, Samora. And when I took a graduate degree in the US in 2014, he unconditionally committed to travel to the University of Houston as my external supervisor, throwing the school’s bureaucrats into a quandary.

They had expected protracted negotiations with his agent over fees, but he had asked for none. Now their dilemma was what to offer him without embarrassing themselves! I left Houston revelling in the fame of the student who brought Ngugi to Houston!

But it wasn’t all show and no work. He thoroughly read my work and provided very constructive feedback, before linking me to his literary agent to ensure the book got published promptly.

In February 2017, we shared the spotlight at the Brooklyn Public Library to launch my historical fiction, Dance of the Jakaranda, symbolically announcing me to the world.

Ngugi and I interacted only as dear sons and fathers do: dancing in Harlem till the small hours of the morning; cutting through Nairobi’s underbelly to the beer halls of Ngara, where author and satirist Wahome Mutahi had popularised travelling theatre. I recall Ngugi summoning a manager and asking why the establishment was so unkempt. “If we want people to take our work seriously,” he counselled, “We must take our work seriously.”

Renowned author Ngugi wa Thiong'o during an interview on February 7, 2019.

He came to my class when I taught at Amherst College, yet another place where he previously taught. Once again, the ease with which I manoeuvred his trip pleasantly surprised the bureaucrats. “I think you should become my agent,” Ngugi joked.

His nickname for me was “Kahiga” a corruption of my first name, Peter and its Greek root, Plato, meaning rock. Kahiga ka bururi, the rock of the nation, he would call me.

“Where are you now?” he would start his conversations, as each of us were constantly on the move, to different parts of the world. “We must ensure someone remains at home,” he would say seriously.

As his health declined and his movement constrained, I recall him sounding subdued. “I am saddened I will never be able to return to Kenya,” he told me early last year. His kidneys had failed, requiring dialysis twice or thrice every week, while relying on life-prolonging drugs for prostate cancer and a heart condition.

On many occasions, he would call me from the hospital bed. “I just wanted to hear a familiar voice, in our language,” he said, expressing the unspoken pain of exile and estrangement. Last year, he revealed he did not have the strength to write another book. His work was done.

But he wasn’t. Even as his strength ebbed, Ngugi remained busy, producing skits and poems that he published far and wide, pillorying politicians as he had done for 60 years. Magooti Ma Mwaura Andu, for instance, released at the height of Gen-Z protests last June, is a playful but biting take on punitive taxes that assailed Kenyans, precipitating the street protests.

He was more exasperated at the seemingly tactless policy decisions by the Kenya Kwanza government that seemed at odds with the nation’s past, such as deploying Kenyan troops to Haiti, the world’s first black republic, at the behest of the United States. “Do they understand that history?” he asked for the umpteenth time.

As his health deteriorated and his world shrunk, our roles changed. He saw the world through my eyes, and those of other close friends in Kenya, whom he regularly phoned for updates. At other times, it was my task to pull my hero from pits of despair, to encourage him to hang in there.

“I have had a revelation,” he said last year, “That dying is part of living.” He elaborated that he hadn’t given up on this life, but he was clear that one transition heralds the beginning of another.

“Are you his son?” someone asked me at a major literature academic conference in December 2016 in Washington, DC. I said I was his literary son.

“He is my sun,” Ngugi smiled. “I walk in his light.”

I have no doubt I shall walk in his light, always.

Peter Kimani is an internationally acclaimed Kenyan author, journalist and editor. He is Professor of Practice at Aga Khan University’s Graduate School of Media and Communications in Nairobi. He previously taught at Amherst College, Duke University and at the Witwatersrand University in South Africa.

You may also enjoy àNgugi wa Thiong’o: The Nobel Laureate who never was