A tribute to Ngugi wa Thiong'o

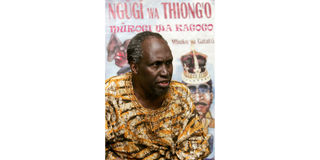

Renowned literature scholar Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o, the Kenyan playwright, novelist and thinker who breathed his last on May 28, has left a huge intellectual gap in Africa’s cultural and political landscape.

Instead of mourning him, I have chosen to celebrate the intellectual legacy of this generous and authoritative African sage I was privileged to have encountered during my undergraduate days at Nairobi University and, much later, as a scholar of Ngugi and African literature generally.

When I arrived in South Africa in 1991, Ngugi was the most widely known African writer in the academy, in spite of apartheid.

As early as 1981, the widely respected South African journal, English in Africa, had dedicated a special issue to his works.

His most widely referenced text then was Decolonising the Mind. Indeed, he is the most widely taught African writer in the global north and the global south, alongside Chinua Achebe – the man who published his award-winning novel, Weep Not, Child under Heinemann African Writers Series.

When the prestigious Cambridge University Press decided to publish world-wide series on ‘Leading Writers in Context”, again it is Achebe and Ngugi who featured from Africa. I am deeply privileged to have been asked to serve as the editor of the volume on “Ngugi in Context”.

Author, playwright and critic Ngugi wa Thiong'o addresses fans on June 13, 2015 during a book signing to celebrate the golden jubilee of his first book 'Weep Not Child' in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi.

His works have been widely translated in several languages across the globe: Japanese, German, Chinese and many parts of Asia, to name but a few.

I hope we will soon see his works getting translated into African languages across the continent. During his last days, he had embarked on translating his novels written in English into Gikuyu.

It needs no emphasis, that Ngugi remains one of the most influential African writers over the last few decades of Africa’s independence, not only for his creative works but also for his wide-ranging contributions on Africa’s cultural thought and political life.

Indeed, the role of the writer in shaping the cultural and political life of his people is an enduring theme in all his works.

He was concerned with the role of culture as a source of historical memory and as a weapon against all forms of oppressive regimes.

But he was also interested in narrative, specifically imaginative literature, as an agent of history and self-definition, an instrument for taming and naming one’s environment.

He was concerned with literature’s role in the restoration of African communities dislocated by colonialism and the repressive post-colonial states that followed. As early as 1972, Ngugi was already drawing attention to how the tyranny of the past exerts itself on his works. He wrote: “The novelist is haunted by a sense of the past.

His work is often an attempt to come to terms with ‘the thing that has been,’ a struggle as it were, to sensitively register his encounter with history, his people’s history” (Homecoming, 39).

Renowned Author Ngugi wa Thiong'o.

For Ngugi then, the novel was an instrument that wills history into being and therefore, as a writer, he always located himself at the intersection of history and literary imagination.

Ngugi always insisted that colonial subjects were detached from their mainstream history and therefore their identity was shaped by forces alien to their local universe. For him, the search for Africa’s identity therefore lay in a reconstructive project to re-assert a radical form of Africa’s historiography conceived from below.

At the heart of his restorative project was also his call for a return to the source, which would also involve the privileging of African languages in the production and consumption of local cultures.

For him, it was only African languages that had the capacity to recover those African cultures repressed by colonialism and to equally carry the weight of a national history and memory. Genuine national literature, Ngugi argued, can only flower in local indigenous languages because literature as a cultural institution works through images and language embodied in the collective experience of a people.

Ngugi always positioned himself as a writer in politics. He was hounded at home by the political establishment and eventually driven into exile.

Kenyan author Ngugi Wa Thiong'o speaks during the launch of his new book "Wizard of the Crow" at the University of Nairobi January 15, 2007.

Little wonder then, that themes of dislocation, abandonment and exile dominates his works, written against the backdrop of authoritarian structures of control and imprisonment.

Ngugi’s early works are heavily weighted towards fiction, and then later lean towards non-fiction. In the 1960s and 1970s, which saw the publication of four novels, two plays and a collection of short stories, Ngugi produced only one volume of essays, Homecoming.

But after his last major work of fiction in English, Petals of Blood (1977), Ngugi wrote a total of five collections of essays as opposed to only three novels, Devil on the Cross (1981), Matigari (1986), and his latest novel, The Wizard of the Crow (Murogi wa Kagogo (2005), written first in Gikuyu before translation.

Kenyan author Ngugi Wa Thiong'o speaks to Reuters during an interview on his newly launched book "Wizard of the Crow" at a bookshop in downtown Nairobi January 16, 2007.

But it was the establishment of a community theatre in his home village of Kamiriithu, and the staging of the play, Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), that really raised the ire of the Kenyan authorities, leading to the banning of the play, his arrest and detention without trial.

It also marked a major turning point in Ngugi’s life when, in prison, he used the time of his incarceration to write his first Gikuyu novel: Caitaani Mutharabaini (Devil on the Cross), on rolls of toilet paper.

Subsequently, it is only his collection of essays that he would continue to write in English, obviously aimed at the academia, with whom he continued to wrestle over a range of cultural and political issues. The joy of reading Ngugi’s essays is that they serve as a theoretical elaboration of themes and topics akin to his narrative.

If Writers in Politics (1981), and Barrel of a Pen (1983) essays seek to question the colonial traditions of English and Englishness inherited at independence, Decolonizing the Mind (1986), and Moving the Centre (1993) push the debate to its limits by insisting that the roots to Africa’s freedom lay in the articulation of a new idiom of nationalism that would liberate the African identities from the prison house of European languages and cultures.

The project should not only involve the privileging of African languages in the making of African cultures, but also the struggle for the realignment of global forces such that societies, which have been confined to the margins, will gradually move to the Centre, to become not just consumers but producers of global culture.

Renowned author Ngugi wa Thiong'o during an interview on February 7, 2019.

It is the denial of the cultural space by the post-colonial state tyranny and global imperialism that Ngugi elaborates on in Penpoints, Gunpoint, and Dreams.

Here, the culture of violence and silence that has come to define the post-colonial state; the state’s desire to saturate the public space with its propaganda, is counterpoised against a radically redemptive art that seeks to erect a new regime of truth by reclaiming and colonizing those spaces through the barrel of the pen.

In his most eloquent collection of essays, symbolically entitled Moving the Centre, Ngugi draws attention to the effect of the colonial archive in arrogating what constitutes the real historical subject to the imperial centre.

When Ngugi calls for moving of the centre, he is in essence trying to suggest that in terms of history and discursive knowledges, the West has always positioned itself as the true self – the centre – while the empire remains the Other and on the periphery.

Celebrated Kenyan author and scholar Prof Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

Indeed, one of the legacies of the colonial encounter is a notion of history as “the few privileged monuments” of achievement, which serves either to arrogate “history” wholesale to the imperial centre or to erase it from the colonial archive and produce, especially in the Empire or the so-called New World Cultures, a condition of “history-lessness”, of “no visible history”.

Both notions are part of the imperial myth of history because history is defined by what is central, not what is peripheral and those not central to an assumed teleology or belief system, are without history.

It seems to me that even a superficial reading of Ngugi’s narrative and his critical essays over the years points to a conscious project of transforming our inherited notions of history, especially the position of the colonial subjects as inscribed within imperial discursive practices.

If the imperial narrative attempted to fix history and to read the empires’ history as the history of the Other, by referring to its set of signs located in its cultural landscape, Ngugi’s position is that the history of Africa need not be contingent upon imperial allegorizing. Allegory here is used to mean a way of representing, of speaking for the ‘Other’, especially in the enterprise of imperialism.

Renowned literature scholar Ngugi wa Thiong’o when he visited Eastleigh Boys High School on June 10, 2015, to celebrate 50 years of his book ‘Weep Not Child’.

Whatever the ideological drifts and shifts in his body of work, Ngugi’s fundamental belief is in the restorative agency embedded in all human cultures, the return of the other to the self.

This is what he celebrates in his theory of globalectics – a theory that seeks to destabilise the privileging Western ways of knowing and instead celebrates those many streams of knowledge, regardless of their origins, as humanity’s collective experience.

The creation of a humanistic wholeness and healing has been at the core of his poetics over the years.

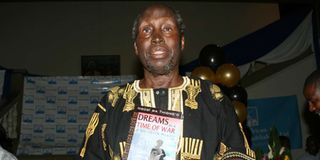

Prof Ngugi wa Thiong'o holds a copy of his autobiography titled Dreams in a Time of War. It was launched in Nairobi on August 19, 2010.

The return to memoirs over the last decade or so was perhaps his last attempt to lay bare his soul and spirit; his life history as fragments of many forces – a rich tapestry into a life crafted around complex and layered forces of family and larger biographical universe.

As a person, Ngugi was profoundly warm and down-to-earth, and always carried himself around with a deep sense of humility and ease, not to mention his infectious laughter and humour. He was simply ordinary – a man of the people. May his legacy live on and his SOUL rest in peace until we meet again in the land of our ancestors.

James Ogude is Professor of African Literatures and Cultures, author of Ngugi’s Novels and African History and Professor and Senior Research Fellow at Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship, University of Pretoria, South Africa